the security research community has proven like never before that cars are vulnerable to hackers—via cellular Internet connections, intercepted smartphone signals, and even insurance dongles plugged into dashboards. Now an automotive security researcher is calling attention to yet another potential inroad to a car’s sensitive digital guts: the auto dealerships that sell and maintain those systems.

At the Derbycon hacker conference in Louisville, Kentucky last week, security consultant Craig Smith presented a tool designed to find security vulnerabilities in equipment that’s used by mechanics and dealerships to update car software and run vehicle diagnostics, and sold by companies like Snap-On and Bosch. Smith’s invention, built with around $20 of hardware and free software that he’s released on GitHub, is designed to seek out—and hopefully help fix—bugs in those dealership tools that could transform them into a devious method of hacking thousands of vehicles.

If a hacker were to bring in a malware-harboring car for service, the vehicle could spread that infection to a dealership’s promiscuous equipment, which in turn would spread the malware to every vehicle the dealership services, kicking off an epidemic of nasty code capable of attacking critical driving systems like transmission and brakes, Smith said in his Derbycon talk. He called that car-hacking nightmare scenario an “auto brothel.”

“Once you compromise a dealership, you’d have a lot of control,” says Smith, who founded the open source car hacking group Open Garages, and wrote theCar Hacker’s Handbook. “You could create a malicious car…The worst case would be a virus-like system where a car pulls in, infects the dealership, and the dealership then spreads that infection to all the other cars.”

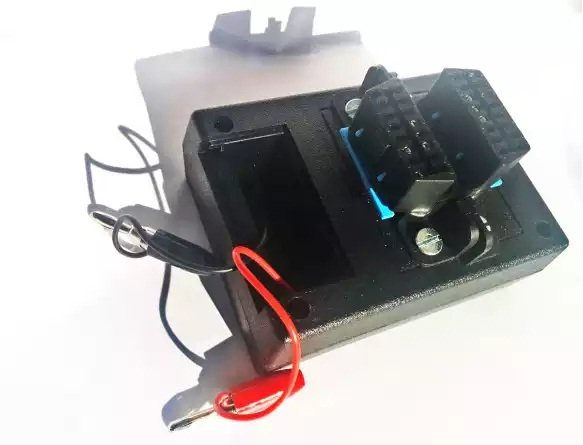

The tool Smith created simulates that kind of attack by impersonating a malicious car. Primarily, it’s a testing device; a way to see what kind of malicious code would need to be installed on a car to infect any diagnostic tools plugged into it. Smith’s device is built from a pair of the OBD2 or On-board Diagnostic ports, the kind that typically appear under a car’s dashboard to offer mechanics an entry point to the CAN network that controls a vehicle’s physical components. It also uses a resistor and some wiring to simulate a car’s internal network and a 12-volt power source. All

of that is designed to impersonate a car when a dealership’s diagnostic tool is plugged into one of the OBD2 ports. The second OBD2 port is used to connect the device to a PC running Smith’s vulnerability scanning software. Smith calls his easily replicated hardware setup the ODB-GW, or Ol’ Dirty Bastard Gateway, a play on a common misspelling of OBD and an homage to the late member of the Wu Tang Clan.

With that ODB-GW plugged into a laptop, Smith’s software can perform a technique known as “fuzzing,” throwing random data at a target diagnostic tool until it produces a crash or glitch that might signal a hackable vulnerability. Smith says he’s already found what appear to be multiple flaws in the dealership tools he’s tested so far: One of the handheld diagnostic tools he analyzed didn’t check for the length of a vehicle identification number. So rather than 14 digits, his car-spoofing device shows that an infected vehicle could send in a much longer number that breaks the diagnostic tool’s software and allows a malware payload to be delivered. Or, Smith suggests, an infected car could overload the dealership’s gadget with thousands of error codes until it triggers the same sort of bug. (Smith says his own tests are still preliminary, and he declined to name any of the diagnostic tools he’s tested so far.) “The dealership tools trust that a car is a car,” says Smith. “They’re a soft target.”

If a hackable bug were found in those dealership tools, Smith says it could be exploited in an actual dealership garage by building an attack into a car itself. He suggests a hacker could plant an Arduino board behind a car’s OBD2 port that carries the malware, ready to infect any diagnostic device plugged into it.

That “auto brothel” attack is hypothetical, but it’s not as farfetched as it might seem. In 2010 and 2011, researchers at the University of California at San Diego and the University of Washington revealed a slew of hackable vulnerabilities in a 2009 Chevy Impala that allowed them to perform tricks like disabling its brakes, although they didn’t name the make or model of the vehicle at the time. One of those attacks was designed to take advantage of an auto dealership: The researchers found that they could break into the dealership’s Wi-Fi network and gain access to the same diagnostic tools Smith has tested via gadgets’ Wi-Fi connections. From there, they could hack any vehicle an infected tool plugged into.

“Any car ever connected to it, it would compromise,” says Stefan Savage, the computer science professor who led the UCSD team. “You just get through the Wi-Fi in the dealership’s waiting room and the attack spreads to the mechanics shop.”

Savage admits that the dealership attack isn’t a particularly targeted one. But that’s precisely what makes it so powerful: he estimates that thousands of vehicles likely pass through a large dealership every month, all of which could be infected en masse. “If the goal is to create mayhem or plant some kind of car ransomware, then going after the dealership is a fine way to get a lot of cars,” Savage says.

In his talk, Smith pointed out that an attack on a dealership’s diagnostic tools wouldn’t necessarily have to be malicious. It could also be aimed at extracting cryptographic keys or code that would let car hacker hobbyists alter their own vehicles for better or worse, changing everything from fuel ratios to emissions controls, as Volkswagen did with its own scandalous nitrogen oxide emissions hack.

But Smith also argues that the diagnostic tool bugs his device susses out represent significant security threats—ones that the auto industry needs to consider as it tries to head off the potential for real-world car hacks. “As more and more security researchers look into automotive security, I want to make sure this isn’t overlooked, as it has been so far,” Smith says. “Ideally I want people doing security audits in the automotive industry to be checking dealership tools, too. This is the way to do it.”

Source:https://www.wired.com/

He is a well-known expert in mobile security and malware analysis. He studied Computer Science at NYU and started working as a cyber security analyst in 2003. He is actively working as an anti-malware expert. He also worked for security companies like Kaspersky Lab. His everyday job includes researching about new malware and cyber security incidents. Also he has deep level of knowledge in mobile security and mobile vulnerabilities.