Ultrasounds emitted by ads or JavaScript code hidden on a page accessed through the Tor Browser can deanonymize Tor users by making nearby phones or computers send identity beacons back to advertisers, data which contains sensitive information that state-sponsored actors can easily obtain via a subpoena.

This attack model was brought to light towards the end of 2016 by a team of six researchers, who presented their findings at the Black Hat Europe 2016 security conference in November and the 33rd Chaos Communication Congress held last week.

Attack relies on ultrasound cross-device tracking (uXDT)

Their research focuses on the science of ultrasound cross-device tracking (uXDT), a new technology that started being deployed in modern-day advertising platforms around 2014.

uXDT relies on advertisers hiding ultrasounds in their ads. When the ad plays on a TV or radio, or some ad code runs on a mobile or computer, it emits ultrasounds that get picked up by the microphone of nearby laptops, desktops, tablets or smartphones.

These second-stage devices, who silently listen in the background, will interpret these ultrasounds, which contain hidden instructions, telling them to ping back to the advertiser’s server with details about that device.

Advertisers use uXDT in order to link different devices to the same person and create better advertising profiles so to deliver better-targeted ads in the future.

Ultrasounds can be reliably used to deanonymize Tor users

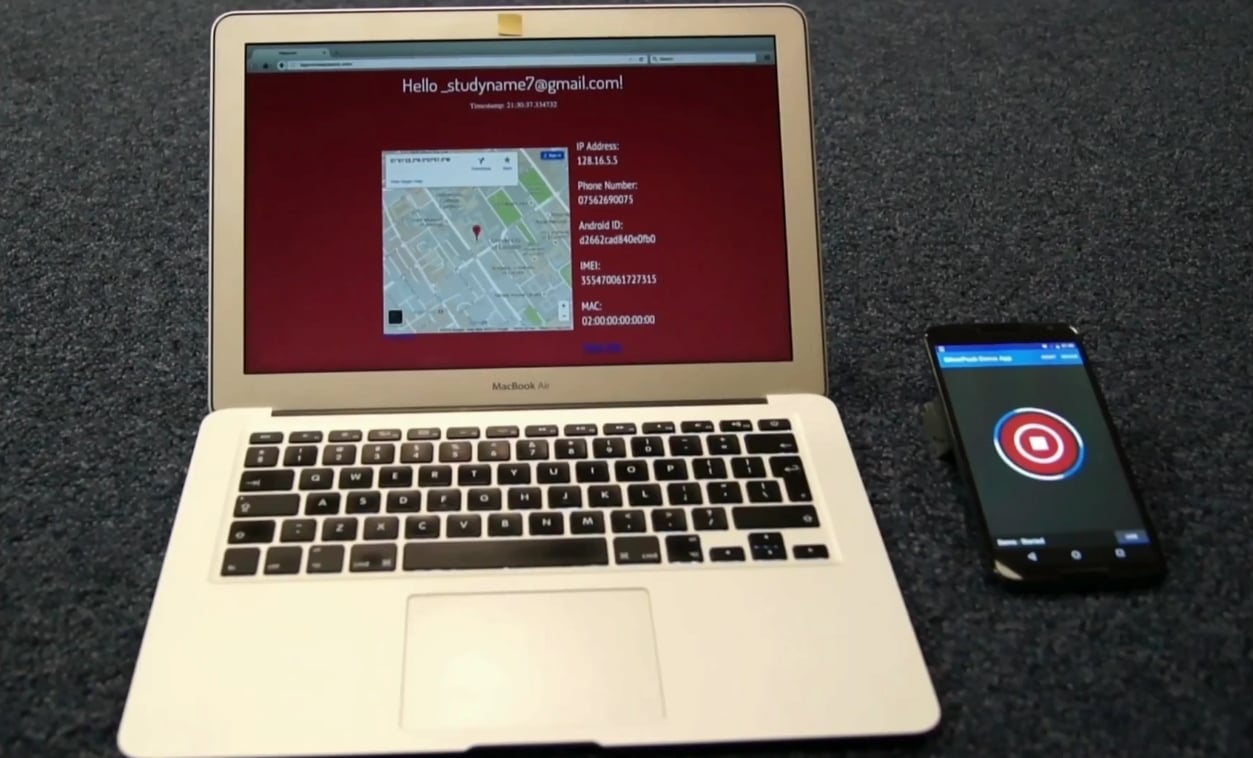

Speaking at last week’s 33rd Chaos Communication Congress, Vasilios Mavroudis, one of the six researchers, detailed a deanonymization attack on Tor users that leaks their real IP and a few other details.

The attack that the research team put together relies on tricking a Tor user into accessing a web page that contains ads that emit ultrasounds or accessing a page that contains hidden JavaScript code that forces the browser to emit the ultrasounds via the HTML5 Audio API.

If the Tor user has his phone somewhere nearby and if certain types of apps are on his phone, then his mobile device will ping back one or more advertisers with details about his device, so the advertiser can build an advertising profile on the user, linking his computer with his phone.

According to Mavroudis, the mobile phone must have an app installed that has embedded one of the many advertising SDKs that include support for uXDT.

At this stage, the state-sponsored actor can simply subpoena a short list of advertisers that engage in this practice and get details about the user’s real-world identity.

In tests carried out by Mavroudis, the researcher has intercepted some of the traffic these ultrasound beacons trigger on behalf of the phone, traffic which contains details such as the user’s real IP address, geo-location coordinates, telephone number, Android ID, IMEI code, and device MAC address.

Multiple ways to deliver the attack

According to Mavroudis, there are multiple ways to deliver these attacks other than social-engineering Tor users to access certain URLs, where these ultrasound beacons can be served.

Researchers say that an attacker can use XSS (cross-site scripting) vulnerabilities to inject the malicious JavaScript code on websites that contain XSS flaws.

Similarly, the attackers could also run a malicious Tor exit node and perform a Man-in-the-Middle attack, forcibly injecting the malicious code that triggers uDXT beacons in all Tor traffic going through that Tor node.

A simpler attack method would also be to hide the ultrasounds, which are inaudible to human ears, inside videos or audio files that certain Tor users might be opening.

The FBI might be very interested in this method and could deploy it to track viewers of child pornography videos on the Tor network, just like it previously did in Operation Playpen, where it used a Flash exploit.

Some mitigations to fight uXDT advertising

Currently, the practice of uXDT is not under any regulation. While the FTC is currently evaluating the impact of uXDT ads, the research team has proposed a series of mitigations that could restrict the free reign this type of advertising currently enjoys.

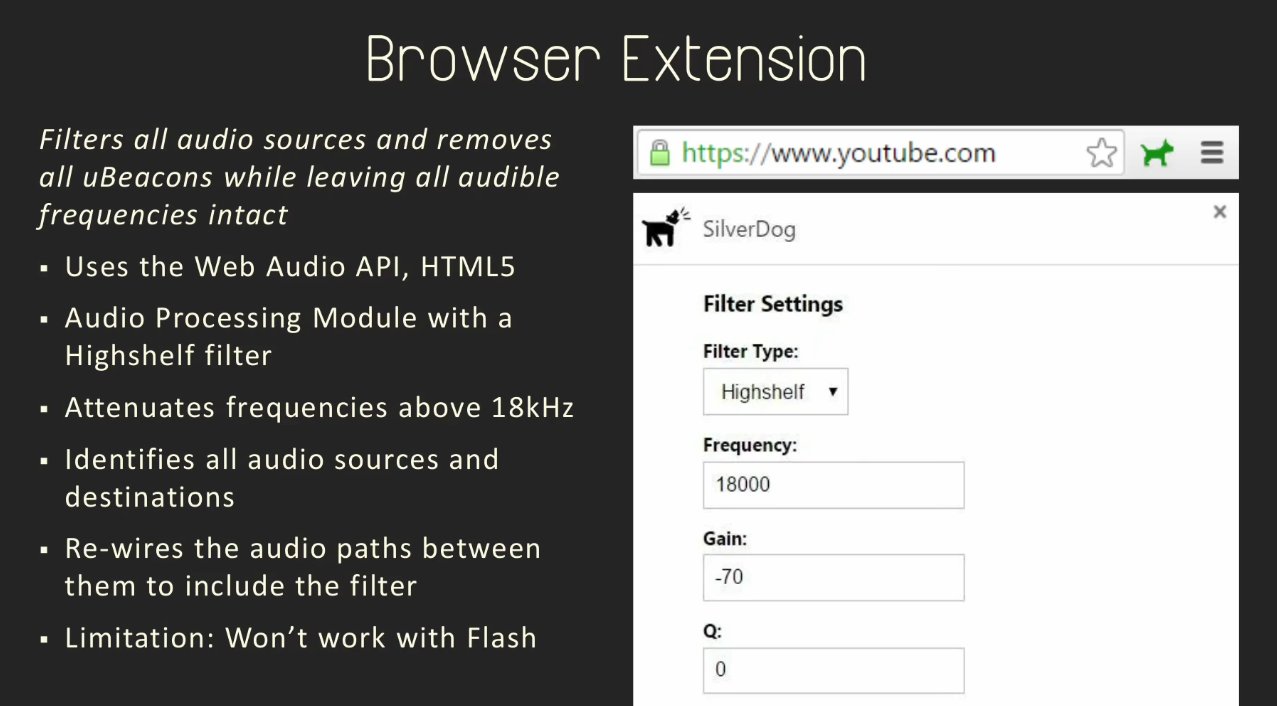

First and foremost, the team created a Chrome browser extension named SilverDog that filters all the HTML5 audio played through the browser and removes ultrasounds.

Unfortunately, this extension doesn’t work with sounds played back via Flash, and can’t protect Tor Browser users, a browser based on Firefox.

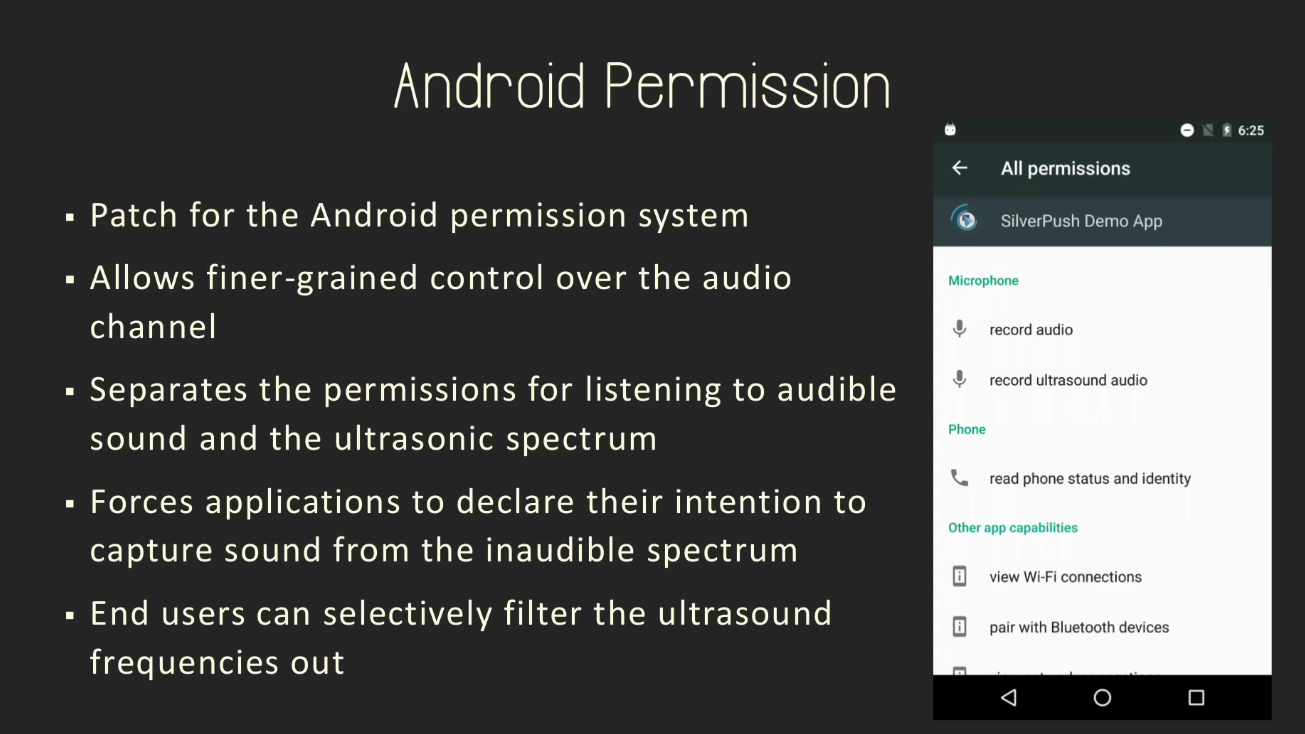

The researchers also propose a medium-term solution such as the introduction of a new query in the Android permissions model that explicitly informs users that an app might listen to ultrasounds.

This permission would allow users to revoke or deny this right from existing or new Android apps they’re installing on their smartphone.

For long-term solutions, the research team advocates for a standardized format for these ultrasound advertising beacons, and OS-level APIs for discovering and managing ultrasound beacons.

Below is Mavroudis presenting his findings at the 33rd Chaos Communication Congress held last week in Germany.

Source:https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.