Recently, we discovered a new Google Android Trojan named “PluginPhantom”, which steals many types of user information including: files, location data, contacts and Wi-Fi information. It also takes pictures, captures screenshots, records audios, intercepts and sends SMS messages. In addition, it can log the keyboard input by the Android accessibility service, acting as a keylogger.

PluginPhantom is a new class of Google Android Trojan: it is the first to use updating and to evade static detection. It does this by leveraging the Android plugin technology. It abuses the legitimate and popular open source framework “DroidPlugin”, which allows an app to dynamically launch any apps as plugins without installing them in the system. PluginPhantom implements each element of malicious functionality as a plugin, and utilizes a host app to control the plugins. With the new architecture, PluginPhantom achieves more flexibility to update its modules without reinstalling apps. PluginPhantom also gains the ability to evade the static detection by hiding malicious behaviors in plugins. Since the plugin development pattern is generic and the plugin SDK can be easily embedded, the plugin architecture could be a trend among Android malware in the future.

Evolution of PluginPhantom

We believe PluginPhantom is a successor to the Android Trojan “Android.Trojan.Ihide”, which was discovered by TrustLook in July of 2016, since they share the same certificate and package name. PluginPhantom not only includes and improved all malicious functionalities from “Android.Trojan.Ihide”, but also adopts a very innovative design architecture. In the new architecture, the original malware app is divided into multiple apps (plugin apps) and a single app (a host app). The host app embeds all plugin apps in resources, which implement different functional modules. After victims install the host app, it can directly load and launch plugin apps without installing plugin apps, by abusing the legitimate open source plugin framework – DroidPlugin [2].

1. Introduction of DroidPlugin:

DroidPlugin is an innovative application-level virtualization/proxy framework, which was originally developed for purposes of hot patching, reducing the released APK size, and removing the 65535 methods limitation. The popular application scenario of DroidPlugin is launching multiple instances of apps on the same device (e.g. using multi-accounts in social apps). Fundamentally, DroidPlugin is very different from the widely known dynamic code loading (e.g. loading a dex or jar file), since it can directly load and launch an app from its APK file without installation. There are five basic concepts or mechanisms in the implementation of DroidPlugin:

- Shared UID. All plugin apps share the same UID with the host app.

- Pre-defined stub components and permissions. The host app has pre-defined components and permissions for plugin apps.

- Dynamic Proxy Hook. The host app has hooked API invocations of plugin apps by the dynamic proxy technique, so that the Android system thinks that all API requests and components are from the host app.

- Resource loading. As the plugin app is not installed in the system, so the host app must take over the process of loading app resources in the plugin app process.

- Component Lifecycle Management. When the component in the plugin process is ready to be destroyed, the corresponding stub component should also be destroyed simultaneously.

2. Plugin Design of PluginPhantom:

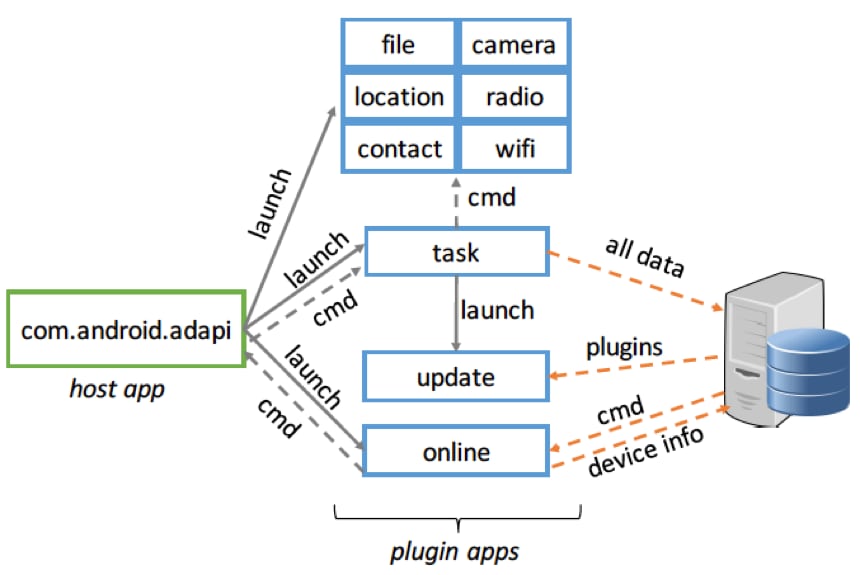

In the plugin design architecture, PluginPhantom has one host app (i.e. the malicious APK we captured) and nine plugin apps that are embedded in the host app as assets files. In these nine plugins, there exists 3 core plugins (“task”, “update” and “online”) and six additional plugins (“file”, “location”, “contact”, “camera”, “radio” and “wifi”), shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Plugin Architecture of PluginPhantom

The host app, as the controller and the entry point of PluginPhantom, schedules plugin apps by launching them and sending commands. In the initialization stage, the host app loads nine APK files in asset files and installs them as plugins in the DroidPlugin framework. Then, the host app can launch and communicate with plugins the same way it would with normal Apps installed on Android.

The online plugin, connects to the command and control (C2) server to upload device information (e.g. the screen state, the battery volume and the free RAM size) and retrieve commands to execute. The online plugin firstly finishes a “ThrowOut” step to probe the remote server by sending the “UUID” (from “java.util.UUID.randomUUID()”) in a UDP socket. If the “UUID” is sent successfully, then, the online plugin continues to utilize the WebSocket to pull the command data from the server.

The task plugin, fetches the command data through the bridge of the host app. According to different command types, the task plugin forwards commands to six additional plugins to launch different attacks. The task plugin also uploads stolen data to the remote server through the WebSocket. In addition, the task plugin launches the update plugin to download new plugin APK files and update plugins, if it receives the “update” command type. Once the update plugin finishes downloading plugins, the task plugin sends a message to the host app to reload and relaunch plugins.

3. IPC and Data Sharing in PluginPhantom:

In the DroidPlugin framework, the host app and all plugin apps share different PIDs, but same UID. Thus, the IPC between the host app and plugin apps or among plugin apps is same as the IPC mechanism in the Android system. The IPC in PluginPhantom includes the Intent and AIDL. The host app can launch all plugin apps by starting the entry service of plugin apps with an Intent. In particular, to keep plugin services alive, the host app uses the alarm manager to restart the entry service of plugin apps in an interval. In addition, AIDL is used for IPC between the host app and plugin apps. For example, “AbsAidl” is used by the task plugin to send commands to the host app for hooking keyboard inputs. The update plugin uses “ClientAidl”, “InfoAidl” and “PluginAidl” to synchronize the updated plugin information with the host app.

Even though the Intent and AIDL can share parts of data, PluginPhantom mainly uses the Content Provider and the file system to share data between the task plugin and six additional plugins. For example, the radio plugin gets commands from the task plugin by the URI “content://***.task.cntPrv/Command”, and stores the command response and recorded audio file paths into the URI “content://***.task.cntPrv/CmdRespond” and “content://***.task.cntPrv/CmdRespondFile” respectively. Later, the task plugin parses last two content providers, and then reads and uploads recorded audio files from the external storage path “/sdcard/AndroidMedia/.audio/record”.

Stealing Information through Plugins

1. File Plugin

The file plugin scans a specific directory and retrieves information (e.g. file name, file type, file size, create time, edit time, file path, canonical path and read state), from the files inside it. It also scans media files in the external storage and can download and delete specific files. During the file operation, the root privilege is used by the file plugin if necessary. In existing samples, PluginPhantom is trying to use the root privilege, but does not root the device. If the attacker wanted root access on the device, they could use the C2 channel to install an APK which exploits an unpatched local root vulnerability, but we have not yet observed this occur with PluginPhantom infections.

2. Location Plugin

The location plugin obtains both fine-grained and coarse-grained location information. It converts coordinates in the Android default geographic coordinate system to coordinates in two other coordinate systems, which are used by Baidu Maps and Amap Maps, the top two navigation apps in China. To successfully obtain the location, the plugin can enable WIFI, GPS (under Android 4.4) and mobile data (under or in Android 5.0) options.

3. Contact Plugin

The contact plugin intercepts incoming SMS and phone calls for specific numbers received from the remote server. To avoid detection, it turns off the ringtone and phone screen and deletes call logs when SMS and phone calls are coming in. The contact plugin also steals call logs, device IDs and contacts info (including deleted contacts) in both the phone contact list and the SIM card contact list. Additionally, it sends SMS messages to specific numbers, which is finished after checking the current phone bill balance.

4. Camera Plugin

The camera plugin takes pictures in the background through either the front or the back camera. It uses a surface view with 0.1*0.1 size for camera previewing, and a full screen Activity with the transparent theme and no title, so victims may be not aware of this behavior. It also takes screen shots by the command “screencap –p” if it has obtained root privileges on the device.

5. Radio Plugin

The radio plugin records the audio in the background with two trigger conditions: commands from the remote server and incoming/outgoing phone calls. To avoid detection, it doesn’t record audio if other apps are also recording.

6. WIFI Plugin

The WIFI plugin steals WIFI information (e.g. SSID, password, IP address, mac address), software information (e.g. app name, version, last update time, is system app), running process information (e.g. PID, process name, app name, app resource path, app data path, timestamp), and trace information (e.g. browser visiting history and bookmarks).

Stealing Keyboard Inputs through Accessibility in the Host App

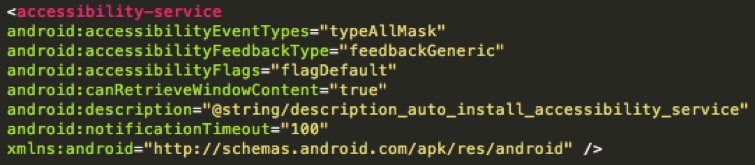

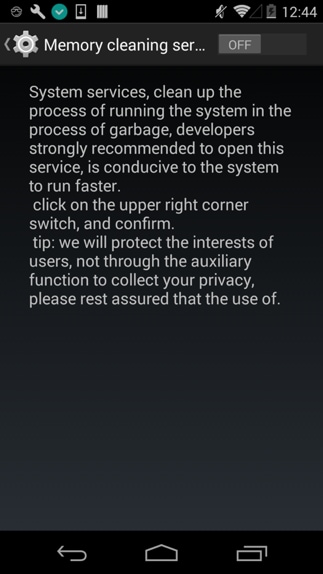

In the host app, a developer defined service named “AutoService” extends the “AccessibilityService” to hook all GUI events in the system (Figure 2). First it needs to trick users into enabling the accessibility permission to this app using it’s description shown in Figure 3, which pretends describes a fake “memory cleaning service.”

Figure 2 Accessibility Service for hooking

Figure 3 Lure users to enable the accessibility service

The host app uses the Android Accessibility feature to hook and operate on the specific Activity and package by referring the class name and package name, for two purposes:

1. Grant or activate if a GUI dialog asks for authorizations. If the text of a clickable button matches keywords in “this.b” (Figure 4), or the text of a checkbox matches keywords “Don’t show this again” in “this.c” (Figure 4), the app will automatically click the button or the checkbox.

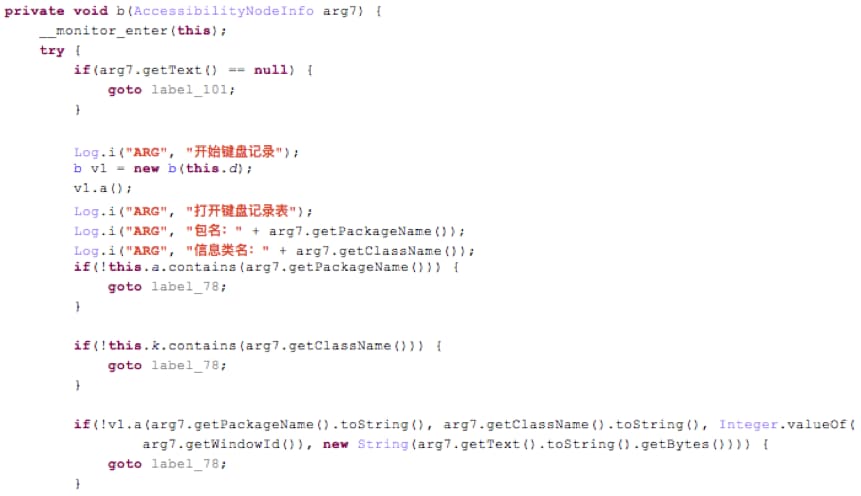

2. Record the keyboard inputs for specific apps. PluginPhantom logs user inputs, such as the text and window id, for all leaf nodes in the UI tree (Figure 5). Thus, the victims’ inputs in the EditText element can be logged. Note that password inputs cannot be logged. The text of password EditText node is always empty since the password attribute of this node is true.

Figure 4 Matched keywords for clicking

Figure 5 Log the text and window id of the UI node

Conclusion

While the Android plugin technology is very hot in the Android app development, it also gives a chance to malware developers to redesign malware in a more flexible way. Like the PluginPhantom family, malware can easily update or add modules by updating or installing plugin apps. In terms of evasion, the plugin malware can hide all malicious behaviors in plugin apps, which can be downloaded and launched to bypass static detection. Additionally, the plugin technology might be a replacement of the repackage technique in the future. The plugin malware only needs to launch the original app as one plugin, and later launch malicious modules as other plugins. Even though the PluginPhantom is the first malware using the legitimate DroidPlugin framework, we will continue to watch and report this threat as attackers may use other plugin frameworks and launch more attacks.

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.