Halfway down the southbound four-lane highway from Cancun to the ancient ruins in Tulum, traffic inexplicably slowed to a halt. There was some sort of checkpoint ahead by the Mexican Federal Police. I began to wonder whether it was a good idea to have brought along the ATM skimmer instead of leaving it in the hotel safe. If the cops searched my stuff, how could I explain having ultra-sophisticated Bluetooth ATM skimmer components in my backpack?

The above paragraph is an excerpt that I pulled from the body of Part II in this series of articles and video essays stemming from a recent four-day trip to Mexico. During that trip, I found at least 19 different ATMs that all apparently had been hacked from the inside and retrofitted with tiny, sophisticated devices that store and transmit stolen card data and PINs wirelessly.

In June 2015, I heard from a source at an ATM firm who wanted advice and help in reaching out to the right people about what he described as an ongoing ATM fraud campaign of unprecedented sophistication, organization and breadth. Given my focus on ATM skimming technology and innovations, I was immediately interested.

My source asked to have his name and that of his employer omitted from the story because he fears potential reprisals from the alleged organized criminal perpetrators of this scam. According to my source, several of his employer’s ATM installation and maintenance technicians in the Cancun area reported recently being approached by men with Eastern European accents, asking each tech if he would be interested in making more than 100 times his monthly salary just for providing direct, physical access to the inside of a single ATM that the technician served.

One of my source’s co-workers was later found to have accepted the bribes, which apparently had only grown larger and more aggressive after technicians in charge of specific, very busy ATMs declined an initial offer.

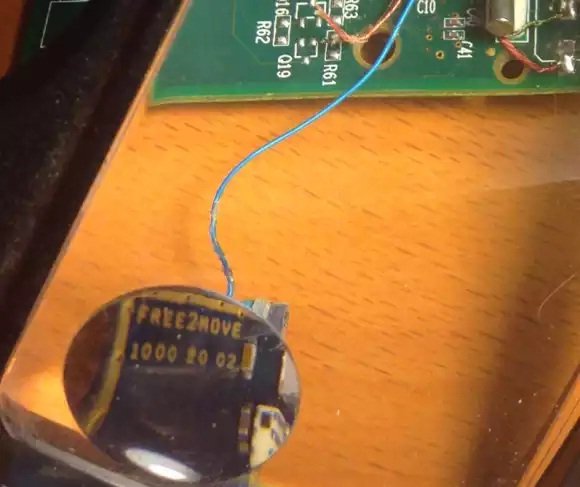

My source said his company fired the rogue employee who’d taken the bait, but that the employee’s actions had still been useful because experts were now able to examine the skimming technology first-hand. The company tested the hardware by installing it into ATMs that were not in service. When they turned the devices on, they discovered each component was beaconing out the same Bluetooth signal: “Free2Move.”

Turns out, Free2Move is the default name for a bluetooth beacon in a component made by a legitimate wireless communications company of the same name. I also located a sales thread in a dubious looking site that specializes in offering this technology in mini form for ATM PIN pads and card readers for $550 per component (although the site claims it won’t sell the products to scammers).

The Bluetooth circuit boards allegedly supplied by the Eastern Europeans who bribed my source’s technician were made to be discretely wired directly onto the electronic ATM circuit boards which independently serve the machine’s debit card reader and PIN pad.

Each of the bluetooth circuit boards are tiny — wafer thin and about 1 cm wide by 2 cm long. Each also comes with its own data storage device. Stolen card data can be retrieved from the bluetooth components wirelessly: The thief merely needs to be within a few meters of the compromised ATM to pull stolen card data and PINs off the devices, providing he has the secret key needed to access that bluetooth wireless connection.

Even if you knew the initial PIN code to connect to the Bluetooth wireless component on the ATM —the stolen data that is sent by the bluetooth components is encrypted. Decrypting that data requires a private key that ostensibly only the owners of this crimeware possess.

These are not your ordinary skimming devices. Most skimmers are detectable because they are designed to be affixed to the outside of the ATMs. But with direct, internal access to carefully targeted cash machines, the devices could sit for months or even years inside of compromised ATMs before being detected (depending in part on how quickly and smartly the thieves used or sold the stolen card numbers and PINs).

Not long after figuring out the scheme used by this skimmer, my source instructed his contacts in Cancun and the surrounding area to survey various ATMs in the region to see if any of these machines were emitting a Bluetooth signal called “Free2Move.” Sure enough, the area was blanketed with cash machines spitting out Free2Move signals.

Going to the cops would be useless at best, and potentially dangerous; Mexico’s police force is notoriously corrupt, and for all my source knew the skimmer scammers were paying for their own protection from the police.

Rather, he said he wanted to figure out a way to spot compromised ATMs where those systems were deployed across Mexico (but mainly in the areas popular with tourists from Europe and The United States).

When my source said he knew where I could obtain one of these skimmers in Mexico firsthand, I volunteered to scour the tourist areas in and around Cancun to look for ATMs spitting out the Free2Move bluetooth signal.

I’d worked especially hard the previous two months: So much so that July and August were record traffic months for KrebsOnSecurity, with several big breach stories bringing more than a million new readers to the site. It was time to schedule a quasi-vacation, and this was the perfect excuse. I had a huge pile of frequent flier miles burning a hole in my pocket, and I wasted no time in using those miles to book a hotel and flight to Cancun.

CANCUN

There are countless luxury hotels and resorts in Cancun, but it turned out that the very hotel I picked — the Marriott CasaMagna Hotel — had an ATM in its lobby that was beaconing the Free2Move signal! I had only just arrived and had potentially discovered my first compromised ATM.

However, I noticed with disappointment that for some reason all of my Apple devices — an iPhone 5, a late-model iPad, and my Macbook Pro — had trouble reliably detecting and holding the Free2Move signals from one of the two ATMs situated in the hotel lobby.

I decided that I needed a more reliable (and disposable) phone, so I hopped in the rental car for a quick jaunt down the road to the local TelCel store (TelCel is Mexico’s dominant mobile provider and a company owned by the world’s second-richest man — Carlos Slim). After perusing their phones, I selected a Huawei Android phone because — at around USD $117 — it was among the cheapest smartphones available in the store. Also, the phone came with plenty of call minutes and a semi-decent data allowance, so I could now avoid monstrous voice and data roaming charges for using my iPhone in Mexico.

Nearby the TelCel store was Plaza Caracol — a mall adjacent to a huge tourist nightlife area that is boisterous and full of Americans and Brits on holiday. The car parked in the mall’s garage, I pulled out my new Huawei phone and turned on its bluetooth scanning application. The first ATM I found — a machine managed by ATM giant Cardtronics — quickly showed it was beaconing two Free2Move signals.

Returning to the Marriott hotel, I found that the two Free2Move bluetooth signals showed up consistently and reliably on my new phone’s screen after about 5 seconds of searching for nearby bluetooth connections. The compromised ATM in the hotel also was a Cardtronics system.

At this point, I went to the front desk, introduced myself and asked to speak to the person in charge of security at the CasaMagna. Before long, I was speaking with no fewer than six employees from the hotel, all of us seated around a small coffee table overlooking the crystal-blue ocean and the pool. I explained the situation and everyone seemed to be very concerned, serious, asking smart questions and nodding their heads.

A man who introduced himself as the hotel’s loss prevention manager disclosed that Marriott had recently received complaints from a number of guests at the hotel who saw fraud on their debit cards shortly after using their ATM cards at the hotel’s machine. The loss prevention guy said the company responsible for the ATM — Cardtronics — had already sent someone out to review the integrity of the machine, but that this technician could not find anything wrong.

[SIDE NOTE: That technician may have only inspected the exterior of the machine before giving it a clean bill of health. Another explanation is that the technician that was sent to find skimming devices didn’t report their presence because he was the one who installed them in the first place!]

That same day, I phoned Giovanni Locandro, senior vice president of North American business development at Cardtronics. He told me the company conducts periodic “sweeps” in Mexico to look for skimming devices on its machines and that it was in the process of doing one at the moment down there, although he didn’t acknowledge whether he was familiar with the exact scheme I was describing.

“We are doing another sweep as we speak down there,” Locandro said. “We do random sweeps, especially in tourist areas to check for those devices. But we haven’t heard of any cards being cloned. Any devices we receive we take those to our internal security folks, and then we contact the authorities.”

I showed the hotel folks the bluetooth beacons emanating from the ATMs in the lobby, and showed them how to conduct the same scans on their phones. Everyone roundly agreed that the technician had to be called again. But there were two ATMs in the lobby — one dispensing Mexican Pesos and another dispensing only dollars. How to know which ATM is compromised, they asked? Unplug them one by one, I replied, and you’ll see very quickly which cash machine is hacked because the bluetooth beacon would shut off.

Despite more head nods and a round of verbal agreement from the hotel staff that this was a good idea, to my surprise nobody at the hotel bothered to touch the machine for two more days. I watched countless people withdraw money from the hacked ATM; some of those I warned while in the lobby were appreciative and seemed to grasp that perhaps it was best to wait for another ATM; others were less receptive and continued with their transactions.

The next morning — after verifying that the hotel’s ATM was still compromised and trying in vain to hail the security folks again at the hotel — I headed out in the rental car. I was eager to visit some of the other more popular tourist destinations about an hour to the south of Cancun, including Playa del Carmen, Tulum and Cozumel. I wanted to see how many of those towns were hacked by this same skimming crew.

Source:https://krebsonsecurity.com/

He is a well-known expert in mobile security and malware analysis. He studied Computer Science at NYU and started working as a cyber security analyst in 2003. He is actively working as an anti-malware expert. He also worked for security companies like Kaspersky Lab. His everyday job includes researching about new malware and cyber security incidents. Also he has deep level of knowledge in mobile security and mobile vulnerabilities.