The term “virtual private network,” or VPN for short, has become almost synonymous with “online privacy and security.” VPNs function by creating an encrypted tunnel through which your data may transit as it moves over the internet. They are designed to protect your privacy and make it impossible for anyone to monitor or access your activity while you are online. But what happens if the same instrument that was supposed to keep your privacy safe turns out to be a conduit for attacks? Introduce yourself to “TunnelCrack,” a frightening discovery that has sent shockwaves across the world of cybersecurity. Nian Xue from New York University, Yashaswi Malla and Zihang Xia from New York University Abu Dhabi, Christina Popper from New York University, and Mathy Vanhoef from KU Leuven University were the ones that carried out the study.

Two serious vulnerabilities in virtual private networks (VPNs) have been discovered by a research team . These vulnerabilities had been dormant since 1996. It is possible to leak and read user traffic, steal information, or even conduct attacks on user devices by exploiting these vulnerabilities, which are present in practically every VPN product across all platforms. TunnelCrack is a combination of two common security flaws found in virtual private networks (VPNs). Even though a virtual private network (VPN) is designed to safeguard all of the data that a user sends, these attacks are able to circumvent this security. An enemy, for example, may take advantage of the security flaws to steal information from users, read their communications, attack their devices, or even just spill it all. Regardless of the security protocol that is utilized by the VPN, the uncovered flaws may be exploited and used maliciously. In other words, even Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) that claim to utilize “military grade encryption” or that use encryption methods that they themselves invented are vulnerable to attack. When a user joins to an unsecured Wi-Fi network, the initial set of vulnerabilities, which they refer to as LocalNet attacks, is susceptible to being exploited. The second group of vulnerabilities, which are known as ServerIP attacks, are susceptible to being exploited by shady Internet service providers as well as by unsecured wireless networks. Both of these attacks involve manipulating the routing table of the victim in order to deceive the victim into sending traffic outside the secured VPN tunnel. This enables an adversary to read and intercept the data that is being sent.

The video that may be seen below demonstrates three different ways in which an attacker might take advantage of the disclosed vulnerabilities. In the first step of the attack, the LocalNet vulnerability is exploited to force the target to leak communications. This is used to intercept sensitive information that is being transferred to websites that do not have enough security, such as the victim’s account and password being exposed. They also demonstrate how an adversary may determine which websites a user is accessing, which is something that is not generally achievable when utilizing a virtual private network (VPN). Last but not least, a modification of the LocalNet attack is used in order to prevent a surveillance camera from alerting its user to any unexpected motion.

As the demonstration indicates, the vulnerabilities in the VPN may be exploited to trivially leak traffic and identify the websites that an individual is accessing. In addition, any data that is transferred to websites with inappropriate configurations or that is supplied by applications that are not secure may be intercepted.

Users may protect themselves by keeping the software for their VPNs up to date. Additionally, any data that is transferred cannot be stolen if a website is correctly set using HTTP Strict Transport protection (HSTS) to always utilize HTTPS as an additional layer of protection. These days, around 25 percent of websites are built in this manner. In addition, a few of browsers will now display a warning to the user if HTTPS is not being utilized. Last but not least, while they are not always error-free, most current mobile applications employ HTTPS by default and, as a result, also use this additional security.

In addition to being exploited to attack websites, virtual private networks (VPNs) sometimes defend outdated or less secure protocols, which presents an additional danger. These attacks now make it possible for an adversary to circumvent the security provided by a virtual private network (VPN), which means that attackers may target any older or less secure protocols that are used by the victim, such as RDP, POP, FTP, telnet, and so on.

LocalNet Attacks

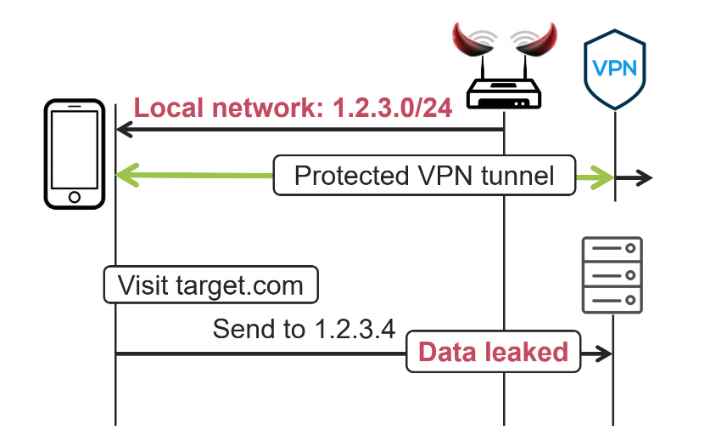

The adversary in a LocalNet attack pretends to be a hostile Wi-Fi or Ethernet network, and they deceive the victim into joining to their network by using social engineering techniques. Cloning a well-known Wi-Fi hotspot, such as the one offered by “Starbucks,” is a straightforward method for achieving this goal. As soon as a victim establishes a connection to this malicious network, the attacker allots the victim a public IP address as well as a subnet. An illustration of this may be seen in the graphic below; the objective of the opponent in this case is to prevent traffic from reaching the website target.com:

The website target.com, which can be seen in the picture to the right, uses the IP address 1.2.3.4. The adversary will convince the victim that the local network is utilizing the subnet 1.2.3.0/24 in order to intercept traffic that is headed toward this website. The victim is told, in other words, that IP addresses in the range 1.2.3.1-254 are immediately accessible inside the local network. A web request will be sent to the IP address 1.2.3.4 if the victim navigates to target.com at this time. The victim will submit the web request outside the secured VPN tunnel because it believes that this IP address is immediately available inside the local network.

An adversary may potentially leak practically all of the victim’s traffic by assigning bigger subnets to the local network they have access to. In addition, although while the LocalNet attack’s primary objective is to send data outside the VPN tunnel, it may also be exploited in such a way as to prevent some traffic from passing through while the VPN is in operation.

ServerIP Attacks

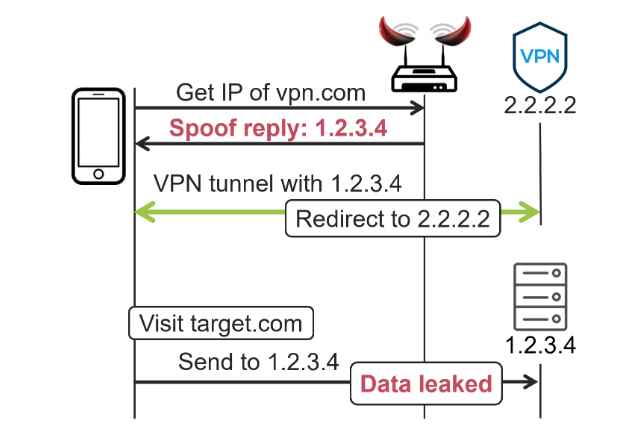

In order to execute a ServerIP attack, the attacker has to have the ability to spoof DNS responses before the VPN is activated, and they also need to be able to monitor traffic going to the VPN server. Acting as a hostile Wi-Fi or Ethernet network is one way to achieve this goal; in a manner similar to the LocalNet attacks, this may also be done. The attacks may also be carried out via an Internet service provider (ISP) that is hostile or by a core Internet router that has been hacked.

The fundamental premise is that the attacker will attempt to impersonate the VPN server by forging its IP address. An attacker may fake the DNS answer to have a different IP address if, for instance, the VPN server is recognized by the hostname vpn.com but its actual IP address is 2.2.2.2. An illustration of this may be seen in the following image, in which the adversary’s objective is to intercept communication sent towards target.com, which has the IP address 1.2.3.4:

The attacker begins by forging the DNS reply for vpn.com such that it returns the IP address 1.2.3.4. This IP address is identical to the IP address of target.com. To put it another way, if you wish to leak traffic towards a certain IP address, you fake that address. After that, the victim will connect to the VPN server that is located at 1.2.3.4. This traffic is then redirected to the victim’s actual VPN server by the adversary, who does this to ensure that the victim is still able to successfully build a VPN connection. As a consequence of this, the victim is still able to successfully build the VPN tunnel even if they are using the incorrect IP address while connecting to the VPN server. In addition to this, the victim will implement a routing rule that will direct all traffic destined for 1.2.3.4 to be routed outside of the VPN tunnel.

A web request is now made to 1.2.3.4 whenever the victim navigates to target.com on their web browser. This request is routed outside of the secured VPN tunnel because of the routing rule that prevents packets from being re-encrypted when they are submitted to the VPN server. As a direct consequence of this, the web request is exposed.

The built-in VPN clients of Windows, macOS, and iOS were discovered to have security flaws by this study. Android versions 12 and above are not impacted by this issue. A significant portion of Linux-based virtual private networks (VPNs) are also susceptible. In addition, they discovered that the majority of OpenVPN profiles, when used with a VPN client that is susceptible to vulnerabilities, utilize a hostname to identify the VPN server, which may lead to behavior that is susceptible to vulnerabilities.

In order to keep customers safe, they worked together with CERT/CC and a number of other VPN providers to develop and release security upgrades over the course of a coordinated disclosure period of ninety days. Mozilla VPN, Surfshark, Malwarebytes, Windscribe (which can import OpenVPN profiles), and Cloudflare’s WARP are a few examples of VPNs that have been updated with patches. You can protect yourself against the LocalNet attack even if updates for your VPN are not currently available by turning off connection to your local network. You may further reduce the risk of attacks by ensuring that websites utilize HTTPS, a protocol that is supported by the majority of websites today.

Information security specialist, currently working as risk infrastructure specialist & investigator.

15 years of experience in risk and control process, security audit support, business continuity design and support, workgroup management and information security standards.