Researchers have discovered never-before-seen malware that North Korean hackers have been using to surreptitiously read and download emails and attachments from the GMail and AOL accounts of infected users.

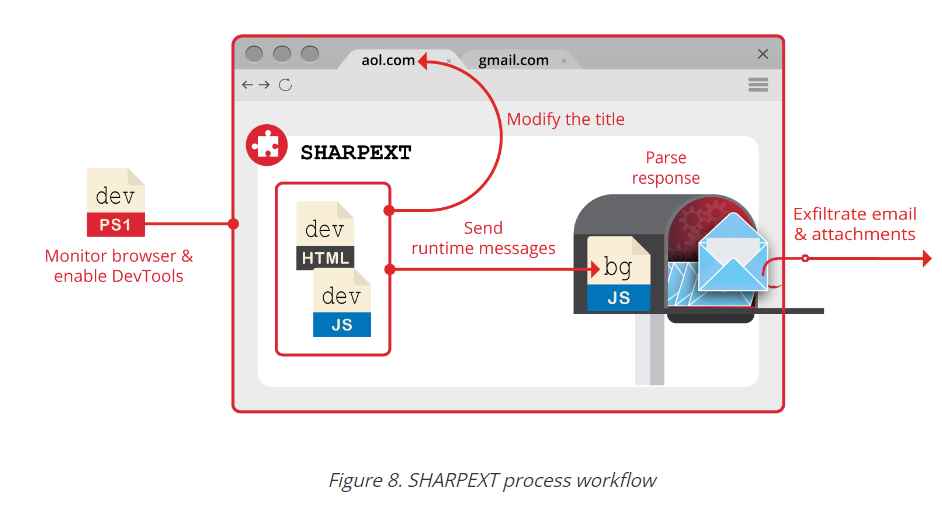

The malware, dubbed SHARPEXT by researchers, uses clever means to install a browser extension for Chrome and Edge browsers, Volexity reported. Email services cannot detect the extension, and since the browser has already been authenticated using existing multi-factor authentication protections, this increasingly popular security measure plays no role in curbing account compromise. The extension is not available from Google’s Chrome Web Store, Microsoft’s Add-ons page, or any other known third-party sources, and does not rely on GMail or AOL Mail failures to install.

The malware has been in use for “more than a year,” Volexity said, and is the work of a hacker group the company tracks as SharpTongue. The group is sponsored by the North Korean government and overlaps with a group tracked as Kimsuky by other researchers. SHARPEXT is targeting organizations in the US, Europe, and South Korea that work on nuclear weapons and other issues that North Korea considers important to its national security.

Volexity president said in an email that the extension is installed “through spear phishing and social engineering where the victim is tricked into opening a malicious document.In its current incarnation, the malware works only on Windows, but he said there’s no reason it can’t be expanded to infect browsers running on macOS or Linux as well.

The blog post added: “Volexity’s own visibility shows that the extension has been quite successful, as logs obtained by Volexity show that the attacker was able to successfully steal thousands of emails from multiple victims through the deployment of the malware. “.

Installing a browser extension during a phishing operation without the end user noticing is not easy. The SHARPEXT developers have clearly paid attention to research showing how a security mechanism in the Chromium browser engine prevents malware from making changes to sensitive user settings. Every time a legitimate change is made, the browser performs a hash of part of the code. At startup, the browser checks the hashes , and if any of them do not match, the browser asks to restore the previous settings.

It notable because instead of stealing users’ email credentials, the malware, which is basically a malicious extension for Chromium-based browsers, reads messages and extracts data from victims’ webmail accounts as they browse their inboxes. SHARPEXT extension is usually installed on the victim’s Windows PC once it has been compromised through some other vulnerability or infection path.

Someone went to Black Hat and had North Korean malware on their PC

The people tasked with defending the Black Hat conference network see a lot of strange, sometimes hostile activity, and this year included malware tied to Kim Jong-un’s agents.

In its second year of helping protect the Network Operations Center (NOC) from the information security event, the IronNet team said it flagged 31 malicious alerts and 45 highly suspicious events, according to the team’s autopsy report.

Of course, not all malware detected in Black Hat is intended to infect devices and perform nefarious acts; some of it comes from mock attacks in classrooms and on the show floor. So while Tor activity and DNS tunneling would probably, and should, raise alarm bells on a corporate network, at the cybersecurity conference they turned out to be standard attendee behavior and vendor demos.

However, security firm hunters (Peter Rydzynski, Austin Tippett, Blake Cahen, Michael Leardi, Keith Li, and Jeremy Miller) said they discovered “several” active malware infections on the network, including Shlayer, SHARPEXT attributed to Korea North and NetSupport RAT.

Let’s start with the code that has ties to the Supreme Leader himself. It looks like someone had SHARPEXT on their machine, either bringing it to the conference or picking it up while they were there, or something was mimicking it, judging from the network traffic.

“During the conference, we observed numerous calls from four unique hosts to three domains associated with the North Korean SHARPEXT malware,” IronNetthreat hunters documented.

“Given the interest shown by North Korean threat actors in compromising security researchers over the past two years, our observation of North Korean SHARPEXT malware on the Black Hat network is notable in itself due to its use by so many cyber researchers and security employees”. according to the IronNet team.

However, they admit that DNS queries to SHARPEXT command and control servers are still “puzzling.” While there were successful DNS responses from these domains, there was no outgoing communication after the DNS lookup.

“Geo-filtering may have been at play here, but that’s not how we’d expect to see it done and it’s not something we see frequently using DNS,” the hunters theorized. “So we don’t have a good answer as to the reason for this activity.”

In addition to SHARPEXT, the NOC also observed a Shlayer malware infection that completely compromised the victim’s macOS computer, we were told. The attendee’s Mac may have been hijacked by software prior to the event. The first hint of malicious activity came in the form of an outgoing HTTP POST alert to api.commondevice[.]com with blobs encrypted data

Further investigation uncovered HTTP GET requests that retrieved a ZIP file, flagged as malicious on VirusTotal, that did not end in “.ZIP”, which was likely an attempt to evade detection. And all of this “closely matching” activity described by Kaspersky in the analysis of the Shlayer Trojan.

In another case of an attendee arriving at the conference with an infected device, someone showed up with NetSupport RAT (also known as NetSupport Manager RAT) on their computer.

This, like many legitimate remote access tools, is frequently co-opted by cybercriminals to take over someone’s machine, snoop on them, and steal information. RATs can be run on various operating systems, including Windows.

He is a well-known expert in mobile security and malware analysis. He studied Computer Science at NYU and started working as a cyber security analyst in 2003. He is actively working as an anti-malware expert. He also worked for security companies like Kaspersky Lab. His everyday job includes researching about new malware and cyber security incidents. Also he has deep level of knowledge in mobile security and mobile vulnerabilities.