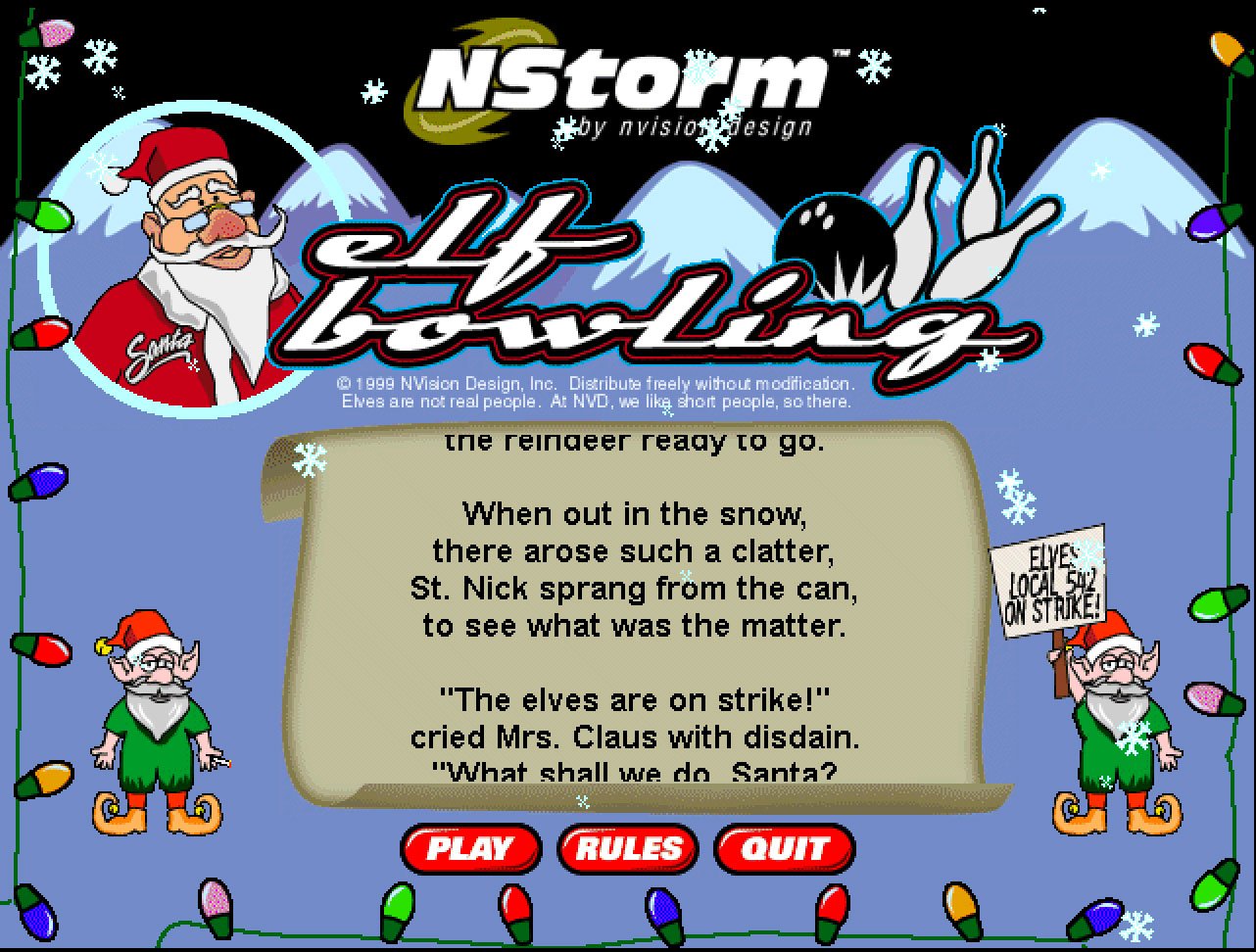

How ‘Elf Bowling,’ the incredibly popular viral game from 1999, became an early victim of what we might now call “fake news.”

It wasn’t even shareware—it was essentially content marketing, an interactive ad designed to promote the creative services of its designer, NVision Design. And on that front, it was a major success. A 1999 article on the Scripps newswire noted that the application was being downloaded at a rate of 900 times per second upon its release in November of that year. The article noted that the company received numerous leads off the release of the game, which won fans for both its animation and sound effects. Per Direct Marketing News, the company, which invested $70,000 to create the game, earned client interest from companies like AT&T and Texas Instruments.

(And later, the game was turned into a movie. A terrible movie, but a movie nonetheless.)

“Millions and millions of people see our work every day,” noted Matt Johnson, then NVision’s director of multimedia. “The 40 people we have here in a little shop in Dallas now have worldwide recognition.”

But not all that recognition was good.

“If you have received Elf Bowling or Frogapult games that have been circulating the internet, or know anyone who has, they MUST BE DELETED before Christmas day. THEY CONTAIN VIRUSES THAT ARE SET TO GO OFF ON CHRISTMAS DAY AND WILL DELETE YOUR HARD DRIVE.”

— A portion of the most common emailed warning to users about Elf Bowling and the game Froagapult, made by the same company. Hoax emails like this one spread widely in the latter part of 1999, giving a hugely popular game a questionable reputation it didn’t deserve. (NVision reportedly was told by a lawyer it had a libel claim, according to a 1999 Morning Call article, but good luck figuring out who made it.) This claim was essentially the equivalent of one guy shouting fire in a crowded theater, and that shout echoing around the world.

No, Elf Bowling didn’t have any viruses in it, and its “spyware” was essentially the game pinging a random server somewhere

So, if it was just an innocuous, funny game, why did Elf Bowling gain a reputation as a piece of malware?

In a lot of ways, the issue cropped up because its insane popularity was being driven by bad behaviors among the millions of people who had only started using the internet a few years prior.

This was before more traditional social media vectors like Facebook and Twitter, and while Flash and Java existed at the time and conceivably would have been a good way to distribute a game like this on the web, Elf Bowling was instead distributed as a Windows executable.

It wasn’t a huge executable, really—at just a megabyte, it was small enough that a few years earlier it might’ve gotten a boost from distribution via floppy. In its own way, it was a slightly more modern twist on what people did with Commander Keen, Jazz Jackrabbit, and Doom just a few years prior.

But the game came to life as millions of people were using email for the first time. While just a few years earlier, chain letters and scams may have gained steam through email or similar tools like Usenet, executables were a new phenomenon for most. And there were already signs that sending executables through email was risky behavior.

Just six months earlier, millions of computers were seriously affected when a Microsoft Word “macro virus” called Melissa tore through the internet. In the ensuing years, email would be the key vector for some extremely damaging viruses, like ILOVEYOU, Sircam, and a virus named for tennis star Anna Kournikova. Their methods were different; their vector, across the board, was the same.

Security experts, understandably had concerns. A 1999 piece written by David Wilson of the Philadelphia Inquirer lays out the concerns like this: This random game which was just emailed you without your consent just so happens to use your internet connection. And it doesn’t tell you off the bat. Ergo: Downloading executables and immediately running them is a bad idea.

Wilson interviewed experts from places like the Electronic Privacy Information Center and Carnegie Mellon University to bolster his case against downloading random apps from any-which-where.

“Experts say the game is a good example of why Internet users should avoid opening unsolicited programs received via email,” Wilson wrote. “It illustrates how computer users often lack privacy protection.”

This is a valid concern, and NVision Design agreed that its game should have had a privacy policy to protect users.

However, the piece somewhat overplayed what the internet connection actually allowed. Per another piece nearby in Allentown, Pennsylvania’s Morning Call that same week, the app simply contacted a server owned by a company to track where the game was being played, and whether the user clicked the link to the company’s website when they were done. The company also used the internet connection to allow users to share high scores, and discussed the potential of distributing updates via an internet connection.

“We were a small company without a budget to get our name out to corporations,” CEO Michael Bielinski said to Direct Marketing News. “We were trying to think of different ways other than putting up banner ads.”

On a base level, yes, the game tracked where a user was coming from, as a primitive form of analytics. But it’s a real stretch to call what they did “spyware.” If you’ve used a website on the internet in the past ten minutes, that page has likely done far worse. Google Analytics does far worse things than this by accident. It was nowhere near as bad as much of the crapware being made at the time, either.

The company denied it was doing anything nefarious other than releasing an offbeat elf bowling game into the wild. It wasn’t like they were the ones who started the email chains—they were distributing the games on their website, a safe and reputable source, after all.

“Absolutely no information is sent back to the company from the user’s computer,” NVision’s Bielinski emphasized to the Inquirer.

Somewhere along the line, though, the legitimate privacy concerns highlighted by the media got turned into something approaching a full-blown hoax. Email, the same medium that made Elf Bowling a hit, gave it an unfounded reputation as a piece of malware. The company spent weeks fighting the claims, which were further ratcheted up by the Inquirer story, which the company reportedly called “irresponsible and inaccurate”—considering it turned the story from a fake virus story into a spyware story, they probably have a case.

“Absolutely no information is collected from your computer and transmitted over the Internet by Elf Bowling or other games. At the beginning of each game, Elf Bowlingtests to see if the computer has a live Internet connection since registering scores online is one of the functions of the games,” the company wrote, according to a Geocities page from the era that collected the company’s correspondence from the time. “To determine if there is a live Internet connection, it sends an HTTP request command to nstorm.com, requesting nstorm.com to send it a blank HTML page. If it receives the blank HTML page, it sets a variable for Internet connectivity to TRUE.”

Symantec, to this day, has a page up on its website emphasizing that NVision’s game were never, at any point, laden with viruses. Sophos says the same thing, though it adds it might have been infected with one later.

To this day, if you look around hard enough on respected sites like TechTarget, Elf Bowling will get accused of being one of the first pieces of spyware. Based on my research, this widely repeated claim appears to be based on a brief mention in a Wikipedia article on spyware that dates to 2005 but was removed in 2006 because there was no source to support the claim that Elf Bowling spied on its users.

It was nothing more than a promotional game that just happened to become insanely popular. It was not spying on you.

Now, were there issues with Elf Bowling and its sibling Frogapult? Yes, there were—though neither were the fault of NVision, when you break it down, and both related to its unusual distribution mechanism.

The first problem is that it’s pretty easy to take an EXE file of a virus or trojan, rename it, and then send that to a user who thinks you’re sending them Elf Bowling—and that’s a concern that was raised by the University of Michigan’s Virus Busters program.

“One needs more than just a file name to identify a piece of software—additional information like the size and date help, and some sort of checksum is necessary before one can have any degree of certainty that what was being described and what is at hand have any correlation with each other,” the university’s Bruce P. Burrell wrote.

The other, more serious problem, was due to the size of the attachment. These days, we think nothing of sending a one-megabyte attachment. But back then, that was a significant size, especially as many offices were only just getting broadband at that point. A 2001 Network World article highlighted how the file created major strain issues on networks far and wide because numerous copies of the executable file were being created. (Apparently, nobody knew what a URL was in 1999.) This was a problem, and Elf Bowling was one of many causes.

It was a security risk and an infrastructure risk, but not because it was Elf Bowling. It was risky because it was an executable being shared like a chain letter on corporate email servers around the country.

But this game’s reputation was forever shattered by some jackass claiming it was a virus, and then by some legitimate reporting that overstated the nature of what the program actually did.

If you look at all the fake news we have going on these days—about topics far more culturally important than elves that get hit with bowling balls by Santa Claus—the parallels are clear. Small pieces of information have a tendency of getting twisted. The loudest claim wins out, even if it’s wrong. And things that are actually true can be twisted and misconstrued under the wrong set of eyes.

This all happened before we gained any of the social mediums we do today. If this is what can happen with just email and Windows, imagine what people might fall for today.

The public deserves to have this wildly popular, if not exactly innovative, game back in its life. And it deserves to have it without the stink of a couple of accusations it never deserved.

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.