A malware coder is injecting megabytes of junk data inside his malicious payloads, hoping to avoid detection by some antivirus solutions or delay investigations of infosec professionals.

Known only as “123”, this malware coder has been active since 2015, when he was first spotted deploying the XXMM malware. His activity falls in the category of targeted attacks, this crook focusing on infecting computers at Japanese companies for the purpose of exfiltrating sensitive data.

123 malware author behind three malware families

According to reports, this threat actor is behind at least three malware families, named XXMM, ShadowWali, and Wali, respectively.

Security firms noted 123’s initial attacks with the XXMM malware in 2015, but they deemed it an usophisticated, albeit very effective, backdoor.

The interest in 123’s activities piqued again over the past month after they unearthed two new malware families created by the same coder.

The first one they’ve discovered was a new backdoor trojan called Wali, which they saw used in live attacks in 2016 and 2017.

Two weeks after Kaspersky’s initial Wali report, security researchers from Cybereason unearthed another backdoor, which they named ShadowWali due to the many features it shared with Wali.

ShadowWali is very likely an earlier version of Wali

Researchers uncovered attacks against Japanese companies with ShadowWali between 2015 and mid-2016, just before the Wali attacks.

Even if there are many differences between the two, experts believe ShadowWali was an earlier version of Wali, a theory supported by the fact that ShadowWali only supported 32-bit architectures, while Wali runs on both 32-bit and 64-bit systems, a clear evolution from the first.

Furthermore, their modus operandi is almost the same. An attack starts after a user downloads the malware from a compromised website. Running the initial payload will start a series of checks, which if satisfied, will end up downloading the final ShadowWali / Wali backdoor.

ShadowWali and Wali are inflated with junk data

Both ShadowWali and Wali are packed inside huge files, ranging from 50 to 200 MBs. Most of the data packed around ShadowWali and Wali is junk data with no real purpose. This is strange, as most malware is usually very small, only a few KBs, and very rarely reaching MB levels.

According to security experts, they believe 123 is under the false impression that by packing malware in large files, security products won’t scan the files, thinking they’re legitimate apps, or due to performance reasons.

Researchers also put forward the theory that another reason why 123 is packing loads of junk data around ShadowWali and Wali payloads is that he is trying to delay investigations from security firms. The reason is that YARA rules, special filters used by infosec professionals to track down malware, are often configured to look at small files, rather than larger files.

ShadowWali/Wali used to download password dumper

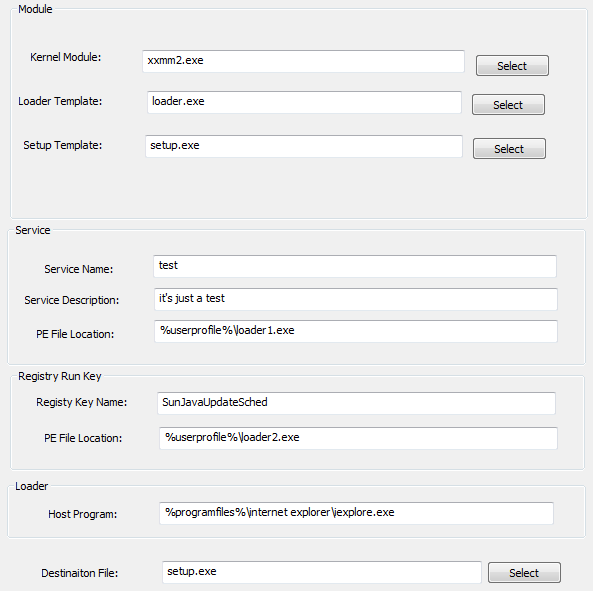

On infected computers, once ShadowWali or Wali are installed, the malware injects itself into other processes. In most infections, the process of choice has been Internet Explorer (iexplorer.exe), but there have been cases where the malware was injected into Windows Explorer (explorer.exe) and the Local Security Authority Subsystem Service (lsass.exe).

After this, the next step is to download several tools to dump credentials from the current PC and explore the local network. To fetch local user credentials, ShadowWali/Wali downloads and installs a module of Mimkatz, a password-dumping utility.

123 then uses these credentials to move laterally inside a company’s network, searching for sensitive information he could steal. What 123 does with this data is currently unknown.

Researcher uncover ShadowWali builder

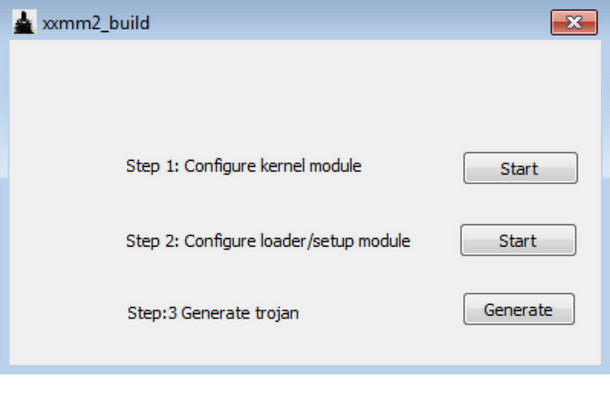

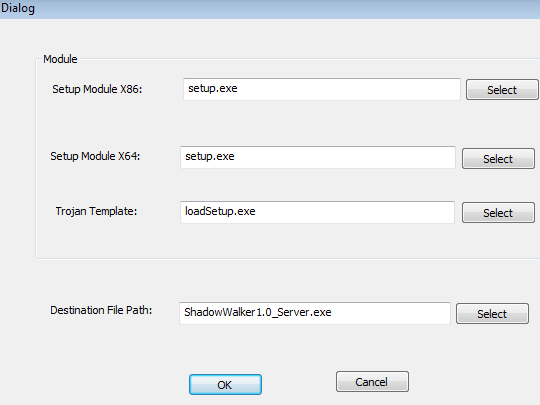

Further sleuthing from Cybereason experts uncovered a utility that appears to be the ShadowWali builder, an application used to assemble the malware.

|

|

|

|

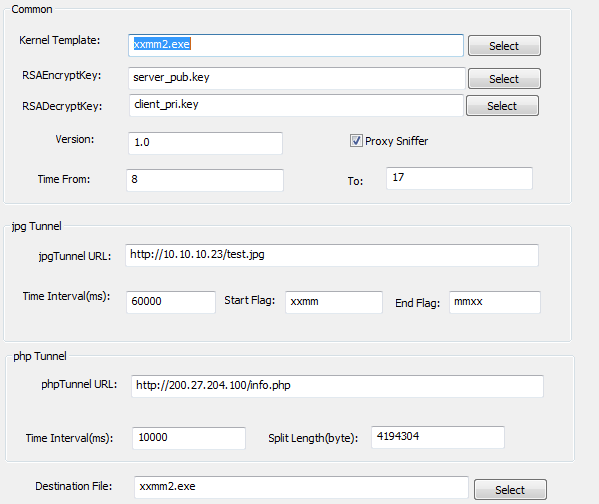

Even if it’s named “xxmm2_build,” Cybereason’s Assaf Dahan says the output of this builder is more consistent with ShadowWali samples, rather than XXMM backdoors.

Further, the usage of the term “rootkit” in the builder’s interface isn’t consistent with the output, as samples operated in user-mode only.

The builder also allowed researchers insight into the malware’s C&C server comms, which rely on steganography to hide second-stage malware downloads inside JPG images, and a PHP tunnel to exchange data with infected hosts.

According to experts, there is also evidence that points to 123 being located in Asia, but no exact and definitive attribute could be made at this point.

Source:https://www.bleepingcomputer.com/news/security/malware-author-inflates-backdoor-trojan-with-junk-data-hoping-to-avoid-detection/

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.