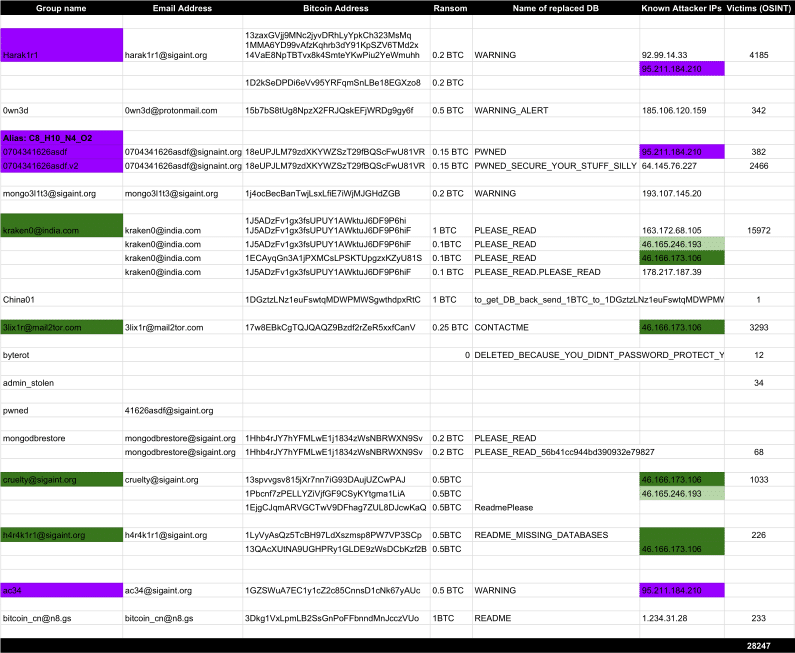

The number of hijacked MongoDB servers held for ransom has skyrocketed in the past two days from 10,500 to over 28,200, thanks in large part to the involvement of a professional ransomware group known as Kraken.

According to statistics provided by two security researchers monitoring these attacks, Victor Gevers and Niall Merrigan, this group is behind around nearly 16,000 hijacked databases, which is around 56% of all ransacked MongoDB instances.

The Kraken group got involved in these MongoDB attacks on Friday, January 6, seeing how successful and profitable previous attacks from other groups had been.

Numbers of hijacked MongoDB servers went from 1,800 to 28,000 in a week

There are currently twelve groups launching attacks on unsecured MongoDB databases. These databases are easy pickings because they’ve been left exposed to Internet connections with no password on the administrator account.

These groups access these unsecured databases, export their content, and leave a message behind asking for a ransom payment in order to return the data.

According to the Gevers and Merrigan, in recent days, some groups aren’t even downloading the data, but simply deleting it. Nevertheless, many companies paid to get their data back.

These attacks started around Christmas 2016, and initially, they were small in nature and carried out by one group alone, nicknamed Harak1r1.

Attacks intensified last Monday when Bleeping Computer first reported on these events after Harak1r1 successfully compromised around 1,800 MongoDB installations.

Two days later, the number of groups involved in these hijacking attacks grew to three, and by Saturday there were eight groups, with the number of hijacked databases reaching 10,500 servers.

Professional ransomware group gets involved in MongoDB attacks

As the number of hijacked servers grew to over 28,000, the massive surge that took place over the weekend was driven by the involvement of Kraken, a group that has been previously involved with the distribution of “classic” Windows ransomware.

The connection between the Windows ransomware and the MongoDB attacks comes from the usage of the same email address in both attacks: kraken0@india.com.

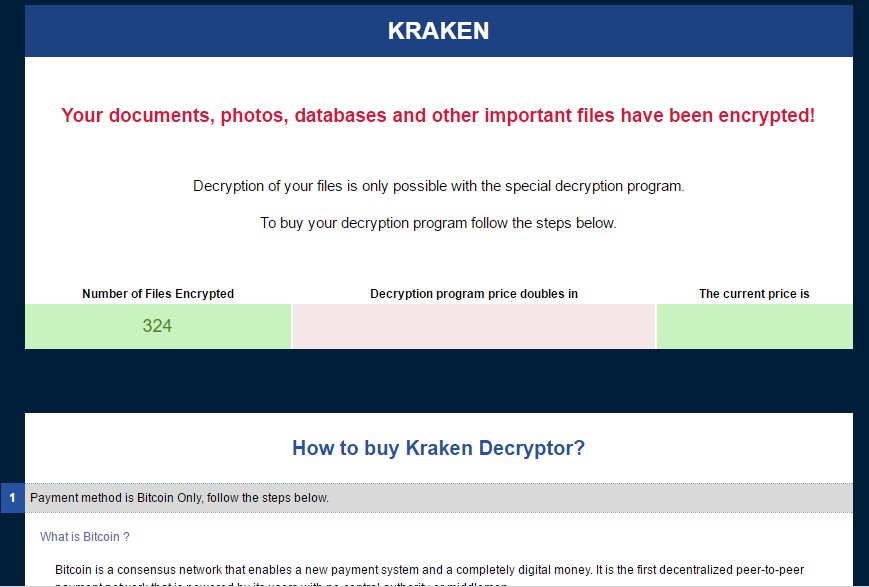

Prior to the attacks on MongoDB databases, the group had created and deployed its own brand of ransomware, known as the Kraken Ransomware.

According to Michael Gillespie, the creator of ID-Ransomware, a service that allows for ransomware victims to detect which ransomware family has locked their files, the Kraken Ransomware was never “a hit.”

“[Kraken was] very small, only a handful of submissions to ID-Ransomware,” Gillespie said, “about 8 unique IPs from the US, Slovakia, Germany, the Czech Republic, India, and Cyprus.”

That’s 8 Kraken infections between December 1, 2016, and January 3, 2017, which is a laughably small number. Other, more mature ransomware families such as Locky or Cerber infect hundreds of users per week.

It appears that the Kraken group might have found a more lucrative niche in which they can operate.

Kraken group made $6,220 in 3 days of hijacking MongoDB servers

At the time of writing, the group’s Bitcoin wallets received 70 ransom payments from their nearly 16,000 infected victims.

The group, which asks for ransoms between 0.1 and 1 Bitcoin has made 6.89700196 Bitcoin, which is about $6,220. That’s about $2,000 per day, since launching in MongoDB hijacking attacks last Friday.

According to Gevers and Merrigan, the group has been launching attacks from the same IP address as other groups.

“Attacker’s IP 46.166.173.106 has been used by multiple groups, which smells like a Ransom Mongo As A Service kind of setup,” Gevers told Bleeping Computer.

Not all victims who paid received their data back

“I am getting negative feedback from victims who pay the Kraken group and get no email response,” Gevers added. “12 victims complained yesterday that they paid and got no response.”

His colleague, Merrigan, added that “one person said they have asked for information and got a response and it looks like they will pay.” So it appears that the Kraken group might be swamped in emails.

Nonetheless, victims should always ask for proof that the hijackers have their database before paying a ransom. In our last articles on MongoDB attacks, we detailed about a turf war going on between these gangs, who are rewriting each other’s ransom notes. This means people might end up paying the ransom to the wrong group, who doesn’t have their data.

As we concluded in our previous piece on this MongoDB debacle, these attacks might end up being a turning point in MongoDB’s history, being hard to imagine that database administrators might expose their MongoDB instances online after these high-profile ransom attacks.

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.