Securing computers has never been easy. It’s especially hard in hospitals. A heart patient undergoing a medical procedure earlier this year was put at risk when misconfigured antivirus software caused a crucial lab device to hang and require a reboot before doctors could continue.

The incident, described in an alert issued by the Food and Drug Administration, highlights the darker side of using computers and computer networks in mission-critical environments. While a computer crash is little more than an annoyance for most people at home or in offices, it can have far more serious consequences in hospitals, power generation facilities, or other industrial settings.

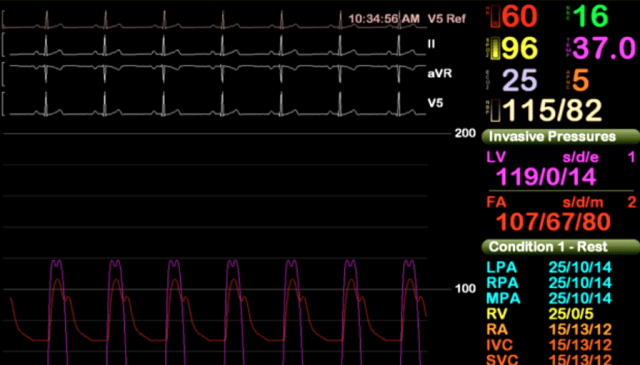

The computer system at issue in the FDA alert is known under the brand name Merge Hemo and is sold by Hartland, Wisconsin-based Merge Healthcare. It comprises a patient data module and a monitor PC that are connected by a serial cable. It’s used to provide doctors with real-time diagnostic information from a patient undergoing a procedure known as a cardiac catheterization, in which doctors insert a tube into a blood vessel to see how well the patient’s heart is working.

In March, an unidentified healthcare provider “reported to Merge Healthcare that, in the middle of a heart catheterization procedure, the Hemo monitor PC lost communication with the Hemo client and the Hemo monitor went black,” the FDA alert stated. “Information obtained from the customer indicated that there was a delay of about 5 minutes while the patient was sedated so that the application could be rebooted. It was found that anti-malware software was performing hourly scans. With Merge Hemo not presenting physiological data during treatment, there is a potential for a delay in care that results in harm to the patient. However, it was reported that the procedure was completed successfully once the application was rebooted.”

The alert continued:

Based upon the available information, the cause for the reported event was due to the customer not following instructions concerning the installation of anti-virus software; therefore, there is no indication that the reported event was related to product malfunction or defect. The product security recommendations, (b)(4), explicitly state, “the intent of these guidelines is to configure the anti-virus software so that it does not affect clinical performance and uptime while still being effective. To accomplish this, the anti-virus software needs to be configured to scan only the potentially vulnerable files on the system, while skipping the medical images and patient data files. Our experience has shown that improper configuration of anti-virus software can have adverse affects [sic] including downtime and clinically unusable performance.”

AV interfering with mission-critical systems isn’t a widely reported problem, but it’s also not unheard of. Michael Toecker, an engineer who specializes in securing industrial control systems, said he’s aware of at least three incidents in North American power-generation facilities in the past five years where antivirus software interrupted computer processes. One of the malfunctions, he said, disrupted what he described as a “mission-critical” process that had the potential to create unsafe conditions if the problem wasn’t remedied promptly. Non-disclosure agreements he signed with the operators of the power-generation facilities bar him from providing further details.

While the home and office PC market often thrives on having a large ecosystem of hardware and software that customers can mix and match, an almost endless list of options can be more of a liability to hospitals and industrial environments. That’s because systems carrying out life-saving procedures or potentially dangerous processes must be extensively tested before being put into production to identify and remedy any potential glitches. To the credit of Merge Healthcare, the Merge Hemo came with safety instructions that AV be set up to skip medical images during scans.

“The engineer who wrote that just earned their entire year’s salary bonus,” Toecker, who works for Context Industrial Security, told Ars.

Catch 22

“The sad part is the customer can’t change it,” Rios told Ars, referring to the typical computerized medical device. “This thing is built to work a certain way. The customer can’t just go in there and start modifying the software. It’s going to break.”

As a result, hospitals and other mission-critical computer users have few options other than to run AV, even though the AV often hasn’t been updated in months or years and its improper use can have catastrophic consequences. A better approach might be for engineers to set up a small list of software the device is permitted to run and to block everything else. Such “whitelisting” techniques are used in some industries but still haven’t been widely embraced by hospitals. The incident disclosed in the FDA alert and a 2013 report finding vulnerabilities in a vast array of medical devices are strong arguments for examining some of these shortcomings and making fundamental changes to the way mission-critical computing is secured in hospitals and other industrial settings.

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.