The Ware Report’s recommendations still important as proven by ransomware and breaches. The National Security Archives at George Washington University has just added a classic text of computer security to its “Cyber Vault” project—the original version of what came to be known as the “Ware Report,” a document published by the predecessor to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency in February 1970. And as much as technology has changed in the 46 years that have passed, the Ware Report would still hold up pretty well today with a few notable edits.

The document, officially entitled “Security Controls for Computer Systems: Report of the Defense Science Board Task Force on Computer Security,” was the result of work undertaken in 1967 at the behest of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA, now DARPA) to deal with the risks associated with the rapid growth of “multi-access, resource-sharing computer systems”—the primordial network ooze from which the Internet would be born. Authored by a task force led by computer science and security pioneer Willis Ware, the report was a first attempt to take on some of the fundamental security problems facing a future networked world.

The Ware Report included a list of conclusions and recommendations that (based on recent data breaches and security failures) many have failed to take to heart. The first of these is one that recent ransomware attacks seem to show that organizations have forgotten. “Providing satisfactory security controls in a computer system is in itself a system design problem,” Ware wrote in the summary memo accompanying the report. “A combination of hardware, software, communication, physical, personnel and administrative-procedural safeguards is required for comprehensive security. In particular, software safeguards alone are not sufficient.”

Another set of conclusions of the Ware Report also rings true today: while “contemporary technology” could make a closed system (one without network connections, locked in a room in a building) “acceptably resistant to external attack, accidental disclosures, internal subversion and denial of use to legitimate users,” it couldn’t do so for an “open environment, which includes uncleared users working at physically unprotected consoles connected to the systems by unprotected communications”—in other words, anything connected to the Internet today that allows open access to the Web and e-mail.

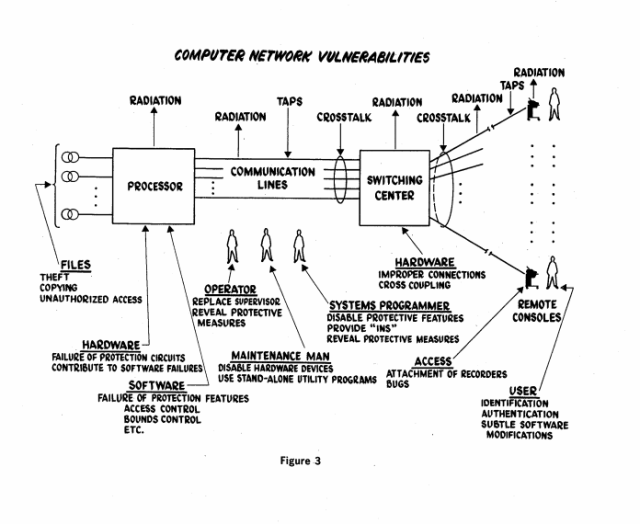

Ware and his co-authors outlined what remain the most common vulnerabilities of computer networks today: accidental exposure or destruction of data by a system failure or user or administrative error, active attacks that exploit weaknesses in user credentials or deliberate or accidental flaws in software (including “unauthorized entry points… created by a system programmer who wishes to provide a means for bypassing internal security controls and thus subverting the system”), and “passive subversion”—collection through passive monitoring of network traffic or electromagnetic emanations from computer or network equipment. While the specifics of some of the “leakage points” detailed by the task force have changed to some degree, many of the problems persist—and are actively exploited by the National Security Agency and other intelligence organizations to gain covert access today, as detailed in leaked documents from an NSA catalog and demonstrated by the devices created by hardware hackers for the “NSA Playset.”

The Ware Report’s outline of what it takes to create a secure system also remains relevant:

The system should be flexible; that is, there should be convenient mechanisms and procedures for maintaining it …The system should be responsive to changing operational conditions, particularly in time of emergency. The system should be auditable…The system should be reliable from a security point of view. It ought to be fail-safe in the sense that if the system cannot fulfill its security controls, cannot make the proper decisions to grant access, or cannot pass its internal self-checks, it will withhold information from those users about which it is uncertain, but ideally will continue to provide service to verified users. The system should bemanageable from the point of view of security control. The records, audit controls, visual displays, manual inputs, etc., used to monitor the system should be supplemented by the capability to make appropriate modifications in the operational status of the system in the event of catastrophic system failure, degradation of performance, change in workload, or conditions of crisis, etc. The system should be adaptable so that security controls can be adjusted to reflect changes in the classification and sensitivity of the files, operations, and the needs of the local installation. The system must be dependable; it must not deny service to users…’The system must automatically assure configuration integrity. It must self-test, violate its own safeguards deliberately, attempt illegal operations, monitor communication continuity, monitor user action, etc., on a short time basis.

Much of the thinking behind the Ware Report was incorporated into the “Rainbow Series” of Defense Department regulations for trusted computer systems, including the “Orange Book,” the Trusted Computer System Evaluation Criteria. The report also urged the development of internal and external encryption technologies to protect data on more open systems. So while the document is part of the pre-history of the Internet and outlines issues that are in many ways archaic, its intent still might make good educational reading for mobile application developers and CIOs.

Source:https://arstechnica.com/

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.