ESET researchers receive and analyze thousands of new malware samples every day. Earlier this year, one of them caught our attention because it was not an ordinary executable file, but a preference file used by a specific program. Further analysis quickly revealed the file actually is malicious and exploited a vulnerability in the software in order to execute code while it is parsed.

This article will take a deep dive into how the exploit works and briefly describe the final payload.

Exploit overview

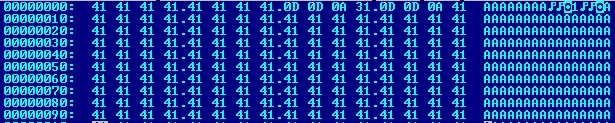

The exploit takes advantage of a buffer overflow vulnerability in the demo version of a program called Uploader!. Developed by ksoft, Uploader! allows its user to upload files to the internet via FTP. Preferences such as the FTP hostname and username are stored in a file named uploadpref.dat. ESET researchers analyzed a preference file that was used to compromise the system when Uploader! is launched.

A proof of concept exploit has been available online since March 2014.

The vulnerability

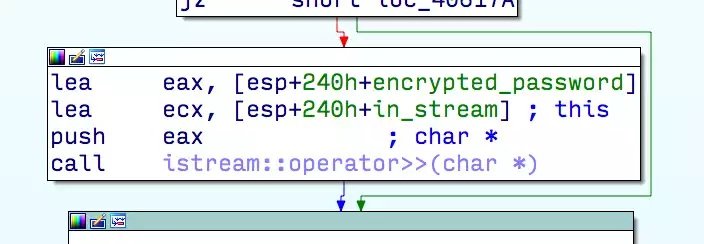

Uploader!’s preference file consists of a set of line-separated strings such as the username and the hostname of the server to which to upload files. The application uses the standard C++ input stream (std::ifstream) to parse the uploadpref.dat file from the disk. While reading strings from the file, all fields are correctly checked for their size by using in_stream.get(buffer, sizeof(buffer), ‘\n’). However, the last field containing the encrypted password uses the following line of code: in_stream >> buffer, where buffer is on the stack. If in_stream.width(…) isn’t called, in_stream >> buffer will result in copying the content of the file to the stack until a white space or the End Of File is reached.

ESET has contacted Ksoft about the issue and a new version of Uploader! (3.6) was released within 24 hours of notification.

How code execution is triggered

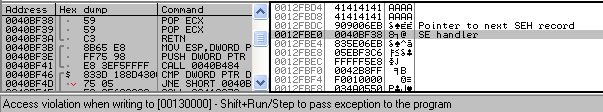

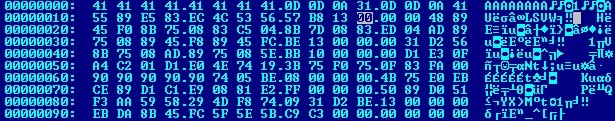

In the case of the exploit we have analyzed, the content of the file is copied onto the stack, beyond the buffer variable, which has a fixed size of 80 bytes. The Structured Exception Handler(SEH) is overwritten and the first shell code is copied. The copy is stopped by an exception when the destination has reach the end of the stack, raising a page violation while trying to write at an invalid address. The exception handler controlled by the attacker will be called. It is set to a pop ecx; pop ecx; ret gadget inside Uploader!’s address space. Finally, the gadget will enable the execution of the first shell code on the stack.

SEH-based exploits are not new. If you are interested in the details, Corelan Team has a very good article on this subject on their website. Structured Exception Handling Overwrite Protection (SEHOP) prevents the execution of such an exploit, but it is not enabled in the Uploader!application and is enabled system-wide only on Windows Server. It is possible to change this setting in EMET’s user interface.

The exploit was likely based on the proof-of-concept exploit mentioned above: although there are 178 pop; pop; ret gadgets in the code, this exploit uses the exact same one found at 0x0040bf38. The other parts such as the shellcode and the next stages were added by the malware author.

Stages

The exploit has multiple stages before the final payload is executed. This section briefly describe each of these steps.

Stage 0

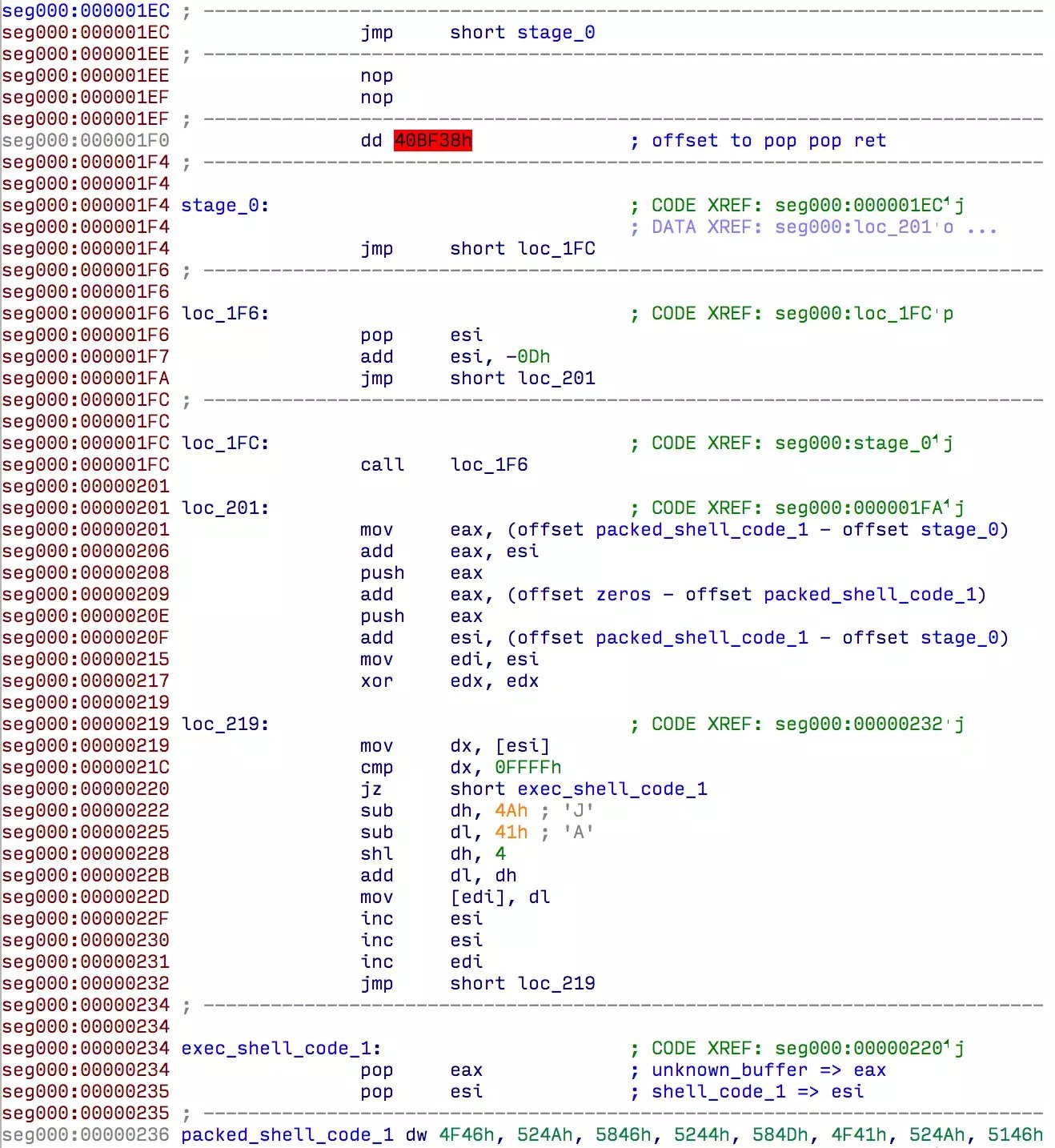

As we said before, the SEH handler points to a pop ecx; pop ecx; ret gadget that will pass the control flow to our first shell code.

These first few instructions unpack the next stage, which we call shell_code_1. It computes a one-byte value out of a two-byte word and writes it at the same memory location. This method allows Stage 1 to be encoded with only uppercase letters in the file.

Stage 1

At the end of this stage the whole content of the uploadpref.dat file is read to memory. It is not obvious at first, because the code searches for Windows API functions in the PEB by using hashes of the DLL names and functions. It calculates the sum of each individual hexadecimal representation of the lowercased characters forming the name of the function and multiplies it by two.

Here is a Python version of the hashing algorithm:

def hash_name(name):

result = 0

for c in name:

result = 2 * (result + (ord(c) | 0x60))

return result

Interestingly, this hashing algorithm is the same that is used as an example in a book by Chris Anley and John Heasman titled “The Shellcoder’s Handbook: Discovering and Exploiting Security Holes”. The C implementation is at page 145 of the 2nd edition.

After the API calls are resolved, shell_code_1 allocates two buffers of the same size as the uploadpref.dat file. The whole content of the file is copied into the first, and the second is left untouched. Then it jumps into the first block at offset 0x10, where the next stage is. Here is a summary in pseudo-C:

HANDLE f = CreateFileA(“uploadpref.dat”, GENERIC_READ, FILE_SHARE_READ, 0, OPEN_EXISTING, 0, 0);

DWORD uploadpref_size = GetFileSize(f, 0);

char * memblock1 = VirtualAlloc(NULL, uploadpref_size, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_READWRITE);

char * memblock2 = VirtualAlloc(NULL, uploadpref_size, MEM_COMMIT | MEM_RESERVE, PAGE_READWRITE);

ReadFile(f, memblock1, uploadpref_size);

stage_2 = &memblock1[0x10];

stage_2(&memblock1[0x650], memblock2);

// memblock2 is also pushed so that returning from stage_2 will jump at offset 0 in memblock2

Stage 2

The function decompresses a buffer at 0x650 into the previously allocated buffer memblock2 with a somewhat inefficient algorithm. Inflated, this buffer is 3,632 bytes long. After this is done, control flow is redirected to the beginning of memblock2, which now contains stage 3.

Stage 3

This stage reopens uploadpref.dat and decompresses a PE file from it, starting at offset 0x1600, into a newly allocated buffer. The decompression algorithm is the same as that used in stage 2.

Then, it creates a new process in suspended mode, and injects and runs the new executable.

The PE file extracted from uploadpref.dat is 56,832 bytes long, and downloads and executes a malicious remote access tool.

Malicious uploadpref.dat file overview

To summarize, here is the whole content of the malicious uploadpref.dat file relative to the different stages of execution.

Malicious payload

Upon successful exploitation, a new process is created with the PE file embedded in the uploadpref.dat file. This new process downloads and executes the final stage: a Remote Administration Tool (RAT) based on Gh0st RAT.

First stage downloader

Persistence

This module maintains persistence on the system by copying the original exploit file and the Upload 3.5!.exe as msfeedssync.exe into the user’s Application Data directory. Then, it adds a shortcut to the executable file inside the the Start menu’s Startup folder. On reboot, the exploit will be triggered again and all the steps will be repeated.

The following files are installed to maintain persistence:

Downloading the payload

Once the persistence of the code is ensured, the executable will fetch the malicious payload via HTTP. Two threads are started at 30-minute intervals. Based on the HTTP user-agent each thread uses, we call the first thread Alan_function and the second one BFunction.

Each thread tries to download the payload from different URLs using the same domain name. Once the downloaded file is decompressed, the two functions will launch the code differently:

- Alan_function expects an executable PE file and will simply launch it.

- BFunction expects a DLL file which it will load and call the TestFunction exported function.

We have only observed the first method of distribution being used in March 2015. The downloaded executable file we have seen is tightly linked to this first stage downloader because its obfuscation method includes the unpacking of a DLL file with an exported function called TestFunction. This DLL could have been delivered to the BFunction thread directly to achieve the same results.

The final payload is a trojan based on Gh0st RAT.

The trojan

The last stage is to drop a variant of remote spying malware based on Gh0st RAT. Gh0st RAThas been thoroughly analyzed and documented by various researchers in the past. If you are interested, links to relevant research are included in the references section below.

Gh0st RAT’s network protocol includes a five-character string to identify the campaign. ThisGh0st RAT variant uses the campaign code A1CEA. It is unclear if the A1CEA campaign is specific to a group. We found a few references online related to A1CEA:

- Sample seen in December 2013 with this campaign code on Malwr

- Snort rule added on March 3rd 2015

- Analysis from Wins in Korea

The C&C server in the sample is www.phw2015.com on TCP port 2015. At the time of writing, the domain resolves to 112.67.10.110.

Other minor modifications to the Gh0st RAT source include:

- Presence of a function that harvests the computer specifications.

- Presence of the exported “TestFunction” that loads the malicious components.

All of Gh0st RAT’s functionalities are present and we have confirmed that the keylogger was enabled.

Conclusion

This exploit is curious because Uploader! is not a massively-deployed application. We are missing some context to understand clearly what happened. Was this exploit used to fool a specific target? The initial attack vector is also unclear: did they use social engineering to persuade the user to replace the preference file with this “special” file? Did they only use this technique as a way to hide the malware’s persistence?

Acknowledgment

Thanks to Hugo Genese for his help on this analysis.

References

Michael G. Spohn (McAfee), Know Your Digital Enemy: Anatomy of a Gh0st RAT,https://www.mcafee.com/ca/resources/white-papers/foundstone/wp-know-your-digital-enemy.pdf, 2012

Snorre Fagerland (Norman), The many faces of Gh0st Rat,https://download01.norman.no/documents/ThemanyfacesofGh0stRat.pdf, 2012

IoCs

Samples

Other

| Mutex | www.phw2015.comwww.phw2015.comwww.phw2015.com |

Network

See also:

- Emerging Threat’s snort rule

2809928 – ETPRO TROJAN PCRat/Gh0st CnC Beacon Request (A1CEA) (trojan.rules)

Source:https://www.welivesecurity.com/

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.