In August I visited the Chaos Communication Camp near Berlin. Once every four years this great and world’s greatest hacker festival is organized. I spoke with a couple of cool Danish hackers there and we talked about internet security and eventually about the security of Danish banks. Seemed like quite a lot of Danish bank have terrible HTTPS connection security (scoring a F on Qualys SSL Labs). That’s a bad sign and my gut feeling was telling me that this wouldn’t be the only security vulnerability they would have.

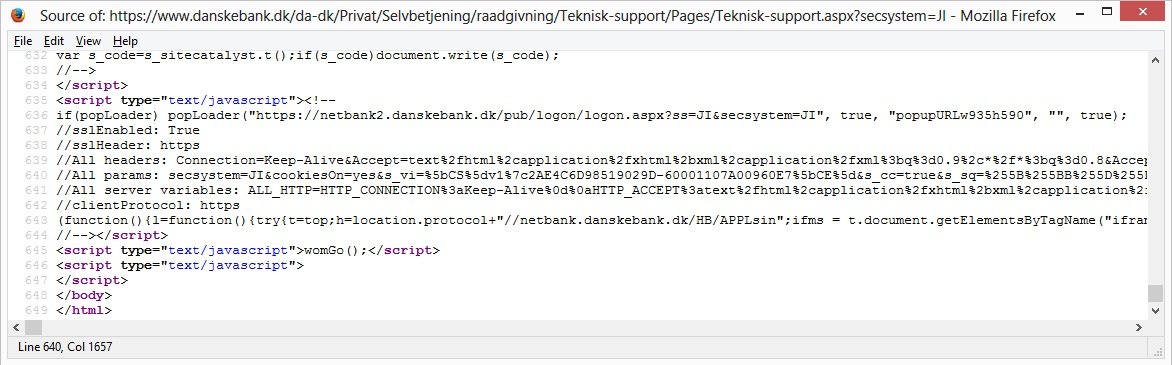

So I opened up the web site of Danske Bank, one of those bank sites. I clicked thru the site and was curious to see how the HTML code looked like, so opened the code of the customer login screen of the banking environment. I scrolled thru the code to get a grasp of the technology used. Then my eye caught JavaScript comments that seemed to contain internal server information. Not just a few variables, but quite a lot of confidential data actually (!). It was in URL encoded format, so I decoded it right away. Really wondering what kind of secrets it contained.

When I decoded it, I was shocked. Is this happening for real? I was less than a minute on their web site. This is just the HTML code of the login screen, one of the most visited pages of Danske Bank’s web site. I never heard of this bank, but my new friends told me it was the biggest bank in Denmark.

The leaked technical information

The HTML code of the login screen that got my attention was the following:

To the average eye, above code looks like gibberish, but I immediately saw words likeHTTP_CONNECTION and HTTP_ACCEPT. That’s strange. These keywords are normally only used on the server itself, and should never been sent to visitors.

Did you notice the horizontal scroll bar in above picture? A lot of code is available if your scroll to your right. In above code a lot of percentage characters (%) are visible and that means the code is URL encoded. When you decode those codes and structure the data, then the following table can be constructed:

| ASP.NET_SessionId | = | kbthxf55aiit4yn0zgx1ks55 |

| APPL_MD_PATH | = | /LM/W5SVC/1255924431/ROOT |

| APPL_PHYSICAL_PATH | = | d:\data\iis\www.danskebank.dk\wwwroot\ |

| AUTH_TYPE | = | |

| AUTH_USER | = | |

| AUTH_PASSWORD | = | |

| LOGON_USER | = | |

| REMOTE_USER | = | |

| CERT_COOKIE | = | |

| CERT_FLAGS | = | |

| CERT_ISSUER | = | |

| CERT_KEYSIZE | = | |

| CERT_SECRETKEYSIZE | = | |

| CERT_SERIALNUMBER | = | |

| CERT_SERVER_ISSUER | = | |

| CERT_SERVER_SUBJECT | = | |

| CERT_SUBJECT | = | |

| CONTENT_LENGTH | = | 0 |

| CONTENT_TYPE | = | |

| GATEWAY_INTERFACE | = | CGI/1.1 |

| HTTPS | = | off |

| HTTPS_KEYSIZE | = | |

| HTTPS_SECRETKEYSIZE | = | |

| HTTPS_SERVER_ISSUER | = | |

| HTTPS_SERVER_SUBJECT | = | |

| INSTANCE_ID | = | 1255724431 |

| INSTANCE_META_PATH | = | /LM/W3SVC/1175724431 |

| LOCAL_ADDR | = | 10.197.22.250 |

| PATH_INFO | = | /da-dk/Privat/Selvbetjening/raadgivning/Teknisk-support/Pages/Teknisk-support.aspx |

| PATH_TRANSLATED | = | d:\dat\iis\www.danskebank.dk\wwwroot\da-dk\Privat\Selvbetjening\raadgivning\Teknisk-support\Pages\Teknisk-support.aspx |

| QUERY_STRING | = | secsystem=JI |

| REMOTE_ADDR | = | 10.197.22.123 |

| REMOTE_HOST | = | 10.197.22.123 |

| REMOTE_PORT | = | 63276 |

| REQUEST_METHOD | = | GET |

| SCRIPT_NAME | = | /da-dk/Privat/Selvbetjening/raadgivning/Teknisk-support/Pages/Teknisk-support.aspx |

| SERVER_NAME | = | www.danskebank.dk |

| SERVER_PORT | = | 80 |

| SERVER_PORT_SECURE | = | 0 |

| SERVER_PROTOCOL | = | HTTP/1.1 |

| SERVER_SOFTWARE | = | Microsoft-IIS/7.5 |

| URL | = | /da-dk/Privat/Selvbetjening/raadgivning/Teknisk-support/Pages/Teknisk-support.aspx |

| HTTP_CONNECTION | = | Keep-Alive |

| HTTP_ACCEPT | = | text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8 |

| HTTP_ACCEPT_LANGUAGE | = | da,en-US;q=0.7,en;q=0.3 |

| HTTP_COOKIE | = | cookiesOn=yes; s_vi=[CS]v1|2ADB987F85111696-6000013120021EC1[CE]; mbox=session#1440619645928-786416#1440611516; s_cc=true; s_sq=%5B%5BB%5D%5D; s_sv_sid=695191168575; QSI_HistorySession=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.danskebank.dk%2Fda-dk%2FPrivat%2FPages%2FPrivat.aspx~1440619560049 |

| HTTP_HOST | = | www.danskebank.dk |

| HTTP_REFERER | = | https://www.danskebank.dk/da-dk/Privat/Pages/Privat.aspx |

| HTTP_USER_AGENT | = | Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; rv:40.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/40.0 |

| HTTP_REVERSE_VIA | = | W93917 |

| HTTP_CLIENTPROTOCOL | = | https |

| HTTP_CLIENTIP | = | 80.166.145.257 |

| HTTP_CLIENTPORT | = | 45483 |

| HTTP_SOPSECRETURNCODE | = | 000 |

| HTTP_SOPGSAFTLNR | = | C002334 |

| HTTP_SOPGSSESSION | = | jYcemDSCIjJk |

| HTTP_SOPLSID | = | WYU2PQGXGYYSWU5344YMAFJZ |

| HTTP_SOPGLOBALUSERID | = | C002334 |

| HTTP_SOPSESMTTS | = | 2015-08-26-20.03.26.132946 |

| HTTP_SOPCENTER | = | 1 |

| HTTP_SOPMVS | = | M2SR |

| HTTP_SOPDB2MEMBER | = | DEP9 |

| HTTP_SOPQMGR | = | QBPL |

| HTTP_SOPFECICS | = | CICRPPI |

| HTTP_SOPTID | = | 2015-08-26-22.07.44.322171 |

| VTI_IS_INCLUDED_PATH | = | 1 |

The server seems to be configured in debug mode and that’s why it’s dumping these variables. I’ve modified above variable values a little bit in order not to give exact internal information (respecting Danske Bank’s security).

Analyzing the data

I saw something strange. My own IP address wasn’t listed in variable HTTP_CLIENTIPand this listed address was also not an internal server IP address. When I translated IP address 80.166.145.257 to the corresponding fully qualified domain name, the result I got was 80-166-145-257-static.dk.customer.tdc.net. Notice the .dk in the result? That means it’s an IP address from Denmark. I live in The Netherlands myself. That probably means that the IP address I’m seeing is from a web site visitor, and very likely a customer of Danske Bank.

If I refreshed the login screen again, I would get to see a different set of data, from another customer. I repeated that a few times and got back different records each time.

This observation is very interesting, but then again: very alarming.

Hijacking bank accounts

Looking further at the data I saw that the variable HTTP_USER_AGENT contains an operating system and web browser that I’m not using. Hold your breath. Then I also saw that variable HTTP_COOKIE was visible and that it was full of information. For those not really familiar with cookies: cookies are the keys that give access to an account that is logged in. So, I’m now looking at the credentials of someone’s online banking account!

I’m shocked. I can’t believe this. It’s so obvious and in plain sight! How come that nobody at Danske Bank noticed this before?

If the customer from the data that we’re seeing is logged in at the moment, and if I copy those cookies and import them into my browser, then I’m also logged in as that customer. That’s how cookies work, and thus that’s how identify theft works.

I had to resist the urge to hijack this bank account to prove my case. If I hijacked this account, that would mean that I’m breaking the law. And that isn’t going to happen.

Reflection on technical data leakage

When looking at the table above there exists two variables that Danske Bank should be very lucky that they were empty: AUTH_USER and AUTH_PASSWORD. If Danske Bank would have used HTTP Basic Authentication technology for internal server network security, the password of it would have been printed in the HTML source code and the gaffe would have been bigger. Talking about luck that that didn’t happen! Or … talking about missing internal network authentication? It’s probably luck (giving them the benefits of the doubt), as I expect them to use a different server authentication method.

Another interesting variable is SERVER_PORT. This one has value 80 and variable HTTPShas value off. This means that on the internal network Danske Bank doesn’t use a secure HTTPS connection to transport customer banking traffic. The HTTPS traffic from customers is offloaded at their network gate and then the traffic is unsecured routed through various servers. Not something that is best practice nowadays from security standpoint. HTTPS should also be applied on internal networks, otherwise network administrators can read and change traffic, and thus the possibility opens for them to hijack customers bank accounts.

The variables HTTP_SOPDB2MEMBER, HTTP_SOPQMGR and HTTP_SOPFECICS indicate that their Microsoft IIS server is connecting to a z/OS server that runs a DB2 database, message queue software and CICS. That’s a pretty normal (but old!) software stack for a bank. Probably also means they’re still using COBOL code on their backend.

Responsible disclosure

I didn’t contacted Danske Bank immediately, as I’ve a very busy professional schedule and not a lot of time for free vulnerability coordination and research. Two weeks after I initially found this critical vulnerability, I took the time to find a way to report it to them (on August 26).

Easier said than done. They don’t have a responsible disclosure process in place, so there was no e-mail address I could mail my findings to. I called a phone number on their web site and the lady that I spoke didn’t seem to understand the problem and said: “our technical guy will look at your finding”. I asked for her e-mail address so I could mail the details to her but she said that wasn’t possible. I didn’t get the feeling I was taken seriously, so I started looking on LinkedIn for IT security personnel that worked at the bank.

Found someone that worked in the security incident response department and mailed him my findings. That worked! I saw that within 24 hours the vulnerability was patched.

Danske Bank responds

I was eagerly looking at my mailbox for feedback on my finding that I just sent them, but that didn’t came soon. After twelve days (on September 7) they finally sent me the following:

Thank you for reporting a potential security vulnerability on our website.

We investigated your report immediately. However, the data you saw was not real customer sessions or data – just some debug information.

Our developers corrected this later that day.

A potential vulnerability? Are you serious? The server was leaking all kinds of highly technical data. And what about using not real customer data? Is it suggested that Danske Bank is using test customer data in their production environment? That would be against all safety guards and all best practices. And creating test cookie data in production in combination with an IP address and user agent? Never seen that one before.

I’m not buying that. Over the last 17 years I’ve performed countless responsible disclosures and developed a good sense when companies are downplaying the situation. Someone at Danske Bank has messed up pretty hard and they’re now covering the situation. That’s not honest and certainly not transparent.

Wrapping up

For at least two weeks, but probably a lot longer, very confidential customer data in the form of session cookies were leaking on Danske Bank’s web site. With these cookies it should have been possible to hijack internet banking accounts of their customers. They closed the security hole quickly, but are now in denial of it.

Source:https://sijmen.ruwhof.net/

Working as a cyber security solutions architect, Alisa focuses on application and network security. Before joining us she held a cyber security researcher positions within a variety of cyber security start-ups. She also experience in different industry domains like finance, healthcare and consumer products.